Farmers Need Help to Survive. A New Crop of Farm Advocates Is on the Way.

by Cara Nixon. This story was originally published by Civil Eats on January 14, 2025.

Farmers with expertise in law and finance have long guided the farming community through tough situations, but their numbers have been dropping. Now, thanks to federally funded training, farm advocates are coming back.

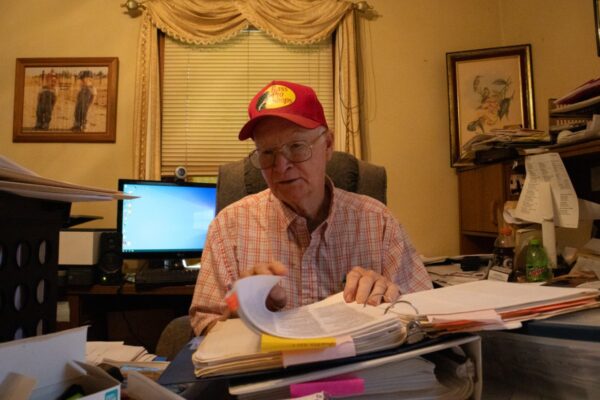

Benny Bunting in his home office in Oak City, NC. Bunting keeps a library of farming regulations and laws, and a binder of relevant documents for each farming family that he has helped. On the desk, he scours federal and state regulations for the exact piece of the legal puzzle that he needs for a farming operation that he is currently helping. (Photo credit: Wayne Gray)

In 2007, fourth-generation farmer Luciano Alvarado Jr. and his family were looking for a fresh start. Their business had been booming in Florida, where they farmed citrus and vegetables. But after a family member died, they decided to pack up and head to land they owned just outside of Fayetteville, North Carolina, to process their loss in a new place.

Alvarado hoped they could turn the acreage into a blueberry farm and make a decent profit. But their fresh start quickly turned sour. The family found themselves in deep financial trouble after learning how different and complicated North Carolina’s loan regulations were from those in their home state. And, still struck with grief, he and his family struggled to make sound financial decisions.

It was by a stroke of luck that Alvarado learned about North Carolina-based Rural Advancement Foundation International-USA (RAFI), a nonprofit which helps farmers in tough situations free of charge. “Well, I’ve got nothing else to lose,” Alvarado recalls thinking.

He called the number he had been given and soon was connected with a farm advocate named Benny Bunting. Farm advocates, often farmers themselves, help their neighbors navigate codes and regulations—pertaining to things like zoning, food safety, and property rights—that can save their operations.

Bunting, now 79, runs a family farm with his son in Oak City, North Carolina, where he once raised poultry and hogs and now grows hemp and corn. During his first day helping the Alvarados untangle their messy financial situation, he sat at their kitchen table for eight hours straight, drinking coffee with them in the morning and sharing dinner with them that night.

If not for that help, “I don’t think we would be having this conversation right now,” Alvarado said. “We could have ended up with nothing.”

Though farm advocates like Bunting have made a massive difference for the farmers they’

ve helped, a good number have aged out of the work or died, leaving a void for farmers in need of guidance. For a while, a lack of funding for these positions—and a shortage of people willing to take up the emotionally taxing and sometimes unpaid work—made it difficult for organizations to recruit these advocates, and the profession was at risk of disappearing altogether.

Luciano Alvarado Jr. shows his son Ruben a successful blueberry crop on their North Carolina farm during the first week of harvest in 2024. Farm advocate Benny Bunting helped the family navigate the financial trouble they faced when they first established the farm after moving up from Florida. (Photo credit: Ruben Alvarado)

Now, a new federal effort is looking to create a fresh team of helpers. In September 2024, the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) pledged $30 million over three years to establish the Distressed Borrowers Assistance Network (DBAN), an initiative designed to connect financially distressed farmers and ranchers with personal assistance to help them regain their footing. A large part of this work consists of recruiting and training a new generation of advocates to help farmers struggling with complex financial and legal issues.

Through a series of cooperative agreements, the USDA’s Farm Service Agency (FSA) is facilitating the network, along with a handful of farmer support organizations and land-grant universities: RAFI, Farm Aid, the University of Arkansas, the University of Minnesota, and the Socially Disadvantaged Farmers and Ranchers Policy Research Center at Alcorn State University in Mississippi.

“It’s a high-stakes kind of work,” said Margaret Krome-Lukens, RAFI’s policy director. “Our goal here is to be able to train folks without having the mistakes that are part of the learning process be those that impact farmers. I have so much admiration for the farm advocates who just sat down and started figuring it out, and I want to give the next generation of farm advocates the benefit of that hard work, experience, and hard-won lessons and knowledge.”

As one of the last experienced farm advocates remaining, Bunting has valuable knowledge that the organizations working to create DBAN hope to capture and pass on to the next generation.

“I don’t feel like I’m overstating in saying that I think Benny is a national treasure,” Krome-Lukens said. “He has a good, strategic mind. He can quote the Code of Federal Regulations to you, chapter and verse. Knowing all that in his head enables him to put the pieces together in a way that sees possibility and if there could be unintended consequences. He also just brings so much compassion.”

The Life of a Farm Advocate

Bunting first got involved with farm advocacy because of his own financial struggles and was recruited by RAFI in the early 1980s. He’s been with the organization ever since, serving as lead farm advocate for the last 20 years. When Bunting is not out working his own fields, he’s advocating for others out of his home office, which is full to the brim with crates and binders of loan regulation information and farm finance manuals.

Over his four decades in the farm advocate profession, Bunting has used his vast knowledge to save many farms—and sometimes, farmers’ lives. On average, he counsels between 75 and 100 farmers each year, devoting around 60 hours to each client. Between 2010 and 2013 alone, he helped preserve an estimated $50 million in assets for farm families, according to RAFI.

While the job once sent him to farms all over the country, Bunting now works within North Carolina, still making home visits. Many people he has helped consider him family. “When we go in with a farmer, most of the time that farmer would call me up after a meeting and say they got the first good night’s sleep that they’d had in months,” Bunting said.

Krome-Lukens said the RAFI team frequently hears that Bunting offers farmers reassurance that was previously out of reach for them. “What happens is, they are very freaked out about their situation, and they talk to Benny, and Benny is not freaked out about it,” she said. “He can help them figure out a plan and next steps, and that takes a farmer from a place of, ‘I have no idea what to do; everything is crashing and burning,’ to seeing potential pathways through.”

The Birth of Farm Advocacy

The role of farm advocate arose during the farm crisis in the 1980s, when farming was in a state of frightening flux, particularly across the South and Midwest. Drought was worsening, interest rates were skyrocketing, and oil prices were increasing, resulting in thousands of foreclosures.

Attorney Sarah Vogel represented North Dakota family farmers in the landmark class-action case Coleman v. Block in 1983, which saved an estimated 16,000 farms from foreclosure. Vogel told Civil Eats that farmers often had to seek finance information themselves and help one another in order to get by.

At the outset, farm advocacy work was often spearheaded by women. In traditional farm households, men would often work longer hours during times of financial stress in hopes of solving their problems, while their spouses would field the delinquent bills piling up on the kitchen table.

It was some of these women, like Oklahoma-based Mona Lee Brock and Minnesota-based Lou Anne Kling, whose activism became legendary. Brock was commonly referred to as “the angel on the end of the line” for setting up an independent 24/7 hotline to talk farmers through mental crises.

And Kling traveled all over her home state saving farms from foreclosure after studying federal regulations and helping one of her struggling neighbors. These women died in 2019 and 2017, respectively, and the farm community feels their absence keenly.

At the peak of the profession, there were probably hundreds of people serving as farm advocates across the U.S., says Jennifer Fahy, co-executive director of Farm Aid, which runs a farmer assistance hotline and financially supports agencies like RAFI that employ advocates.

The role even became institutionalized as some states hired people to work as farm advocates in state programs. Despite this formalization, the profession died out with the end of the farm crisis, Fahy said, and today, only a handful of farm advocates remain.

The need for their services continues, however. Though the debt situation generally has improved for farmers since the 1980s, their security remains vulnerable to market swings, inflation, and other economic factors—as well as weather and climate change.

“There are weather disasters all the time now,” said Krome-Lukens at the end of the 2024 growing season. “We’ve had multiple hurricanes impacting farmers that we work with this season. That was on top of . . . flooding and drought. And you add that commodity growers can’t really have an impact on the prices they’re getting for their crops. Put it all together, and there are a lot of reasons why there are a lot of farmers in financial distress.”

Mona Lee Brock, left, and Lou Anne Kling, right, photographed before their passing in 2019 and 2017, respectively. Brock was commonly referred to as “the angel on the end of the line” for setting up an independent 24/7 hotline to talk farmers through mental crises. Kling traveled all over her home state saving farms from foreclosure after studying federal regulations and helping one of her struggling neighbors. (Photo credit: Rob Amberg for Farm Aid)

Additionally, farm ownership continues to change. The USDA reports that the number of farms in the U.S. has been declining since the early 1970s. And, while small family farms were the norm in the 20th century, many of those operations have been swallowed by corporate operations or disappeared altogether.

One of the biggest needs today, said Zach Ducheneaux, a former farm advocate and now the administrator of the USDA’s Farm Service Agency, is helping farmers prevent foreclosure. “Agriculture isn’t getting any simpler, and neither are the safety net programs designed to support them,” he said. “Access to capital and fair rates, terms, and conditions remain the biggest challenges producers face today.”

Farm advocacy is a tough trade to learn, and, as in Bunting’s case, most of the knowledge is developed through personal experience rather than formally taught by institutions.

In four decades, Bunting has seen many successes but also tragedies. Sometimes he’s called in early enough to save farms from foreclosure, but other times, it’s too late, and a family has to leave their home and their fields behind. In a few instances, Bunting has seen stress mount to the point of death—“from causes that were undiagnosed, let’s put it that way,” he said.

According to the National Rural Health Association, farmers are three and a half times more likely to die by suicide than the general population, and many identify extreme financial stress as the main cause. Farm advocacy, in turn, often extends beyond the financial and legal realms, into the more emotional and personal.

“One way to think about farm advocates is that they exist to help keep people alive, keep them on the farm, and preserve a chance for the future,” Stephen Carpenter, an attorney from the Farmers Legal Action Group (FLAG) in St. Paul, Minnesota, wrote in an article for the Clinical Law Review journal.

Even as Bunting ages, he’s still meeting North Carolina farmers at their kitchen tables and connecting remotely with those outside the state, shepherding them through complicated financial matters, including administrative reviews, mediations over loan disputes, and appealing adverse decisions by various agencies.

The job requires patience and an aptitude for reading records. Regulations change all the time, and Bunting has to keep up with them to stay on his game. Often, by the end of a session, the documents he’s been reviewing are scrawled all over with notes.

“Frankly, it takes a high level of altruism,” Carpenter told Civil Eats. “Nobody’s getting paid very much money. It also takes a lot of substantive knowledge and really, really great skills in dealing with people in terrific crisis.”

Training a New Legion of Advocates

A group of farm advocates gathered in Minnesota in 2015 to talk with a filmmaker about their advocacy work during the Farm Crisis for the Farm Aid documentary, “Homeplace Under Fire.” (Photo credit: Rob Amberg for Farm Aid)

Though federal funding for advocacy instruction has increased in recent years through programs like the USDA’s Farm and Ranch Stress Assistance Network, the training is intensive, and organizations like RAFI have difficulty recruiting and retaining advocates.

Fahy of Farm Aid hopes the influx of federal funding for DBAN, with the FSA’s help, will create “a new legion” of folks who can support farmers in the difficult and essential task of obtaining farm credit.

“It’s a tremendous investment,” she said. “Over the past four years, FSA has made incredible progress in increasing the accessibility and availability of credit for farmers, which is so essential. And this is another step in that process of doing that. Recognizing that navigating their own system via a third party could be helpful is really wonderful. It’s groundbreaking.”

RAFI is in the process of creating two tiers of advocacy curricula. In the first, they will educate people serving in less official and involved capacities, such as helping farmers prepare documents for meetings with FSA loan officers and accompanying them to those appointments to take notes and help remember questions.

The second tier will involve training a smaller set of advocates to a higher level, using resources like a series of recorded Zoom sessions Bunting created for farm advocates during the pandemic. These people might eventually become professional advocates like Bunting, or work for state governments or farmer support agencies. RAFI plans to start this tier by training a cohort of seven advocates in the southeast.

In September, RAFI and Farm Aid held a full-day pilot training for 75 aspiring farmer supporters in Saratoga Springs, New York, and in November, they conducted a second introductory training in Kansas. They plan to offer more trainings in the spring and seek out other promising candidates for the farm advocate job.

Ducheneaux, the first Native American FSA administrator, believes the investment in farm advocates will be vital for all farmers—and for socially disadvantaged farmers in particular. Whether it be for reasons of race, ethnicity, gender, or sexual orientation, these farmers face additional barriers because of systemic discrimination.

“Marginalized producers, regardless of how or why they are marginalized, are inherently less resilient to externalities, and often receive less favorable terms from lenders, vendors, and suppliers alike,” he said.

Additionally, because they do not have as much access to working capital, they often must work off the farm to keep their operations viable. “Financial and business consultants are certainly out of reach,” Ducheneaux said, “and a robust ecosystem of farm advocates can fill in some of those gaps.”

Saving the Farm

Like many farmers across the country, the Alvarados still struggle financially, but through Bunting’s help, they feel they’ve learned from past experiences and better understand how to navigate a complicated system. What’s more, they feel like they have a new member of the family, someone who can help them through future crises.

Last year, for instance, the family faced a shorter-than-usual blueberry season. Bunting helped them develop a plan to increase blueberry acreage while also diversifying their crops and planting blackberries. Now, they feel more hopeful about sustaining their farm.

“We gained a lot,” Alvarado said about Bunting’s help with the farm. “We gained a good friendship, a good bond—so for that, we’re really grateful.”

Bunting, too, finds fulfillment in the work. “Some of my best friends are people that we’ve worked with,” he said. “It’s gratifying to see them come out from being on the brink of the family dissolving, the operation dissolving, everything going down the tube—to see the family and financial operation getting stronger.”

This story was reported as part of U.C. Berkeley Journalism’s Investigative Reporting Program, and through a grant from The SCAN Foundation.

Christina Cooke contributed to the reporting of this story.