Organizing for change: How some activists are responding to police violence

November 9, 2020

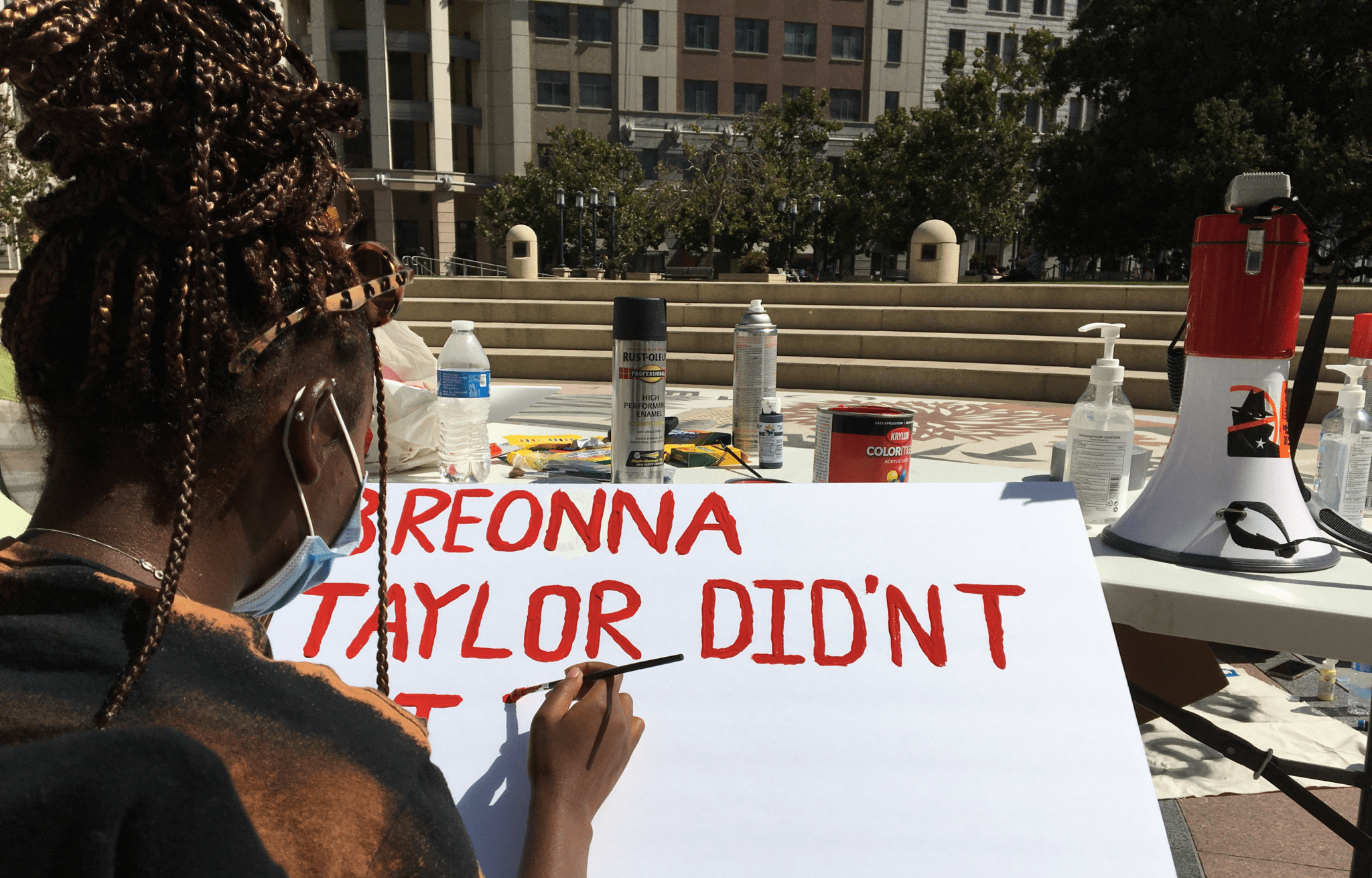

At a boarded up Oakland City Hall, 20-year-old Mara Coleman sits with paint, brushes, markers and white poster board. With a steady hand and careful strokes, Coleman concentrates as she paints the name Breonna Taylor in red paint. This is the location where Coleman met with fellow youth organizers from Abolitionist Movement SF to paint protest signs and memorialize Black victims of police violence–just days after a Kentucky grand jury decided not to prosecute Louisville Metro Police officers for killing Breonna Taylor.

For Coleman, police shootings are not simply cause for national alarm, they’re the catalyst for local action. “I’m not just watching it, I’m actively a part of the change,” she says.

In Oakland, Black residents are disproportionately killed by police. In the past five years, Black people made up 70% of the police’s fatal shooting victims, despite being only 23% of the city’s total population. Since 2015, not a single Oakland Police Department officer has been prosecuted in those cases, according to the Bay Area News Group’s review of law enforcement agency and District Attorney records.

As a result, activists are trying to respond to the immediate needs of the community, while also laying the groundwork for lasting change. From a pop-up protest sign exchange to the defund police campaign, Black organizers in Oakland are working hard to change the status quo. This strategy of engaging in multiple political actions at once can lead to “more enduring” changes, says Sarah A. Soule, a professor of organizational behavior at Stanford University, whose research examines the influence of social movements on policy.

Coleman dedicates hours each Friday afternoon to set up a temporary sign-making station at different locations in the Bay Area. Residents are invited to design, exchange or pick up signs for the next round of protests. The sign-making stations allow participants to channel their grief, share information about resources and organize for future events. As a young Black woman, Coleman is clear about her relation to police violence, partly because she knows her own life could be at risk.

“It’s heavy,” she says. “And sometimes it gets really emotional. It gets heavy because I am Breonna Taylor. I am Jacob Blake. I am George Floyd. It hits close to home.”

Artist Oliwia Olano shares her work from the Abolitionist Movement SF pop-up at Frank H. Ogawa Plaza. Bashirah Mack/Oakland North

Still, Coleman believes almost anyone can make a difference. “You don’t really need much,” she says. “Just get out there.”

That direct approach helped Coleman and youth organizers in her hometown of Seattle, Washington make a difference. There, she participated in mass protests with calls to defund the police which resulted in a 5% decrease in the local police budget. “It’s something,” she says.

Amid cans of paint, hand sanitizer, and poster board, Coleman adjusts her face mask to wipe away the sweat. It’s past noon and the sun is casting its glow on her. When asked where she sees herself in the next few years, Coleman sharply lifts her paintbrush from the white poster board.

“That’s a scary question. I want to see if I can make it to the next few years without getting murdered by the police,” she says. “If I do make it, hopefully I help make some changes in the system.”

Mara Coleman (center) co-organizes a pop-up protest sign exchange at different locations in the Bay Area. Participants are able to gather while adhering to social distance recommendations. Bashirah Mack/Oakland North

At the same time, James Burch, policy director at the Anti-Police Terror Project (APTP), says working to change policing policies is where he’s making a difference. Founded to “end state violence in communities of color,” APTP—a Black-led, multiracial coalition—has spent years developing its policy arm for local impact.

As an organization, APTP began organizing protests following the 2009 killing of Oscar Grant, a Black man, by Bay Area Rapid Transit police. After seeing an opportunity to be more proactive, not just reactive to police shootings, APTP hired Burch, a civil rights lawyer, to focus on local and state policy measures. To date, APTP has co-sponsored several bills, including AB392, the Peace Officer Use of Force Standards (2019), which amended the deadly use of force standard from “objectively reasonable force” to “only when necessary,” for the first time in 150 years.

Since 2016, Burch has led APTP’s Defund OPD campaign to cut Oakland’s police budget in half. Burch says the funds from the police budget should be reinvested in community resources like education and critical infrastructure like fire departments, areas that have seen the impact of budget cuts for years. With the current police budget at around $330 million, Burch says it does not include unauthorized police overtime.

“We’ve never been asking for defund in a vacuum. It’s not just ‘we don’t like cops,’” he says. “It’s that cops don’t keep us safe.” Burch believes it’s in the city’s best interest to prioritize spending differently. “We’re not investing in housing, in mental health services, in youth services, in public transportation, in health care.”

Oakland Police Department did not respond to requests for comment.

While APTP’s Defund OPD campaign seeks to cut the police budget in half, Burch admits his organization’s long term goal is to abolish the police altogether. He says the financial burden on taxpayers to sustain a police department that has not shown reform since a 2003 federal monitor mandate is far too great–the city has already paid more than $70 million in settlements, damages and court fees related to police abuse, misconduct and shootings. Burch believes continuing to fund the department would feed into a cycle of harm.

“We’re not talking about dismantling the entire police department tomorrow,” he says. “What we’re talking about is doing what we think the majority of Oaklanders would agree upon. And we think that everyone would be shocked when they realize how much money goes into things we all agree that cops shouldn’t be doing.”