In Stockton, a Powerful Program to Prevent Violence

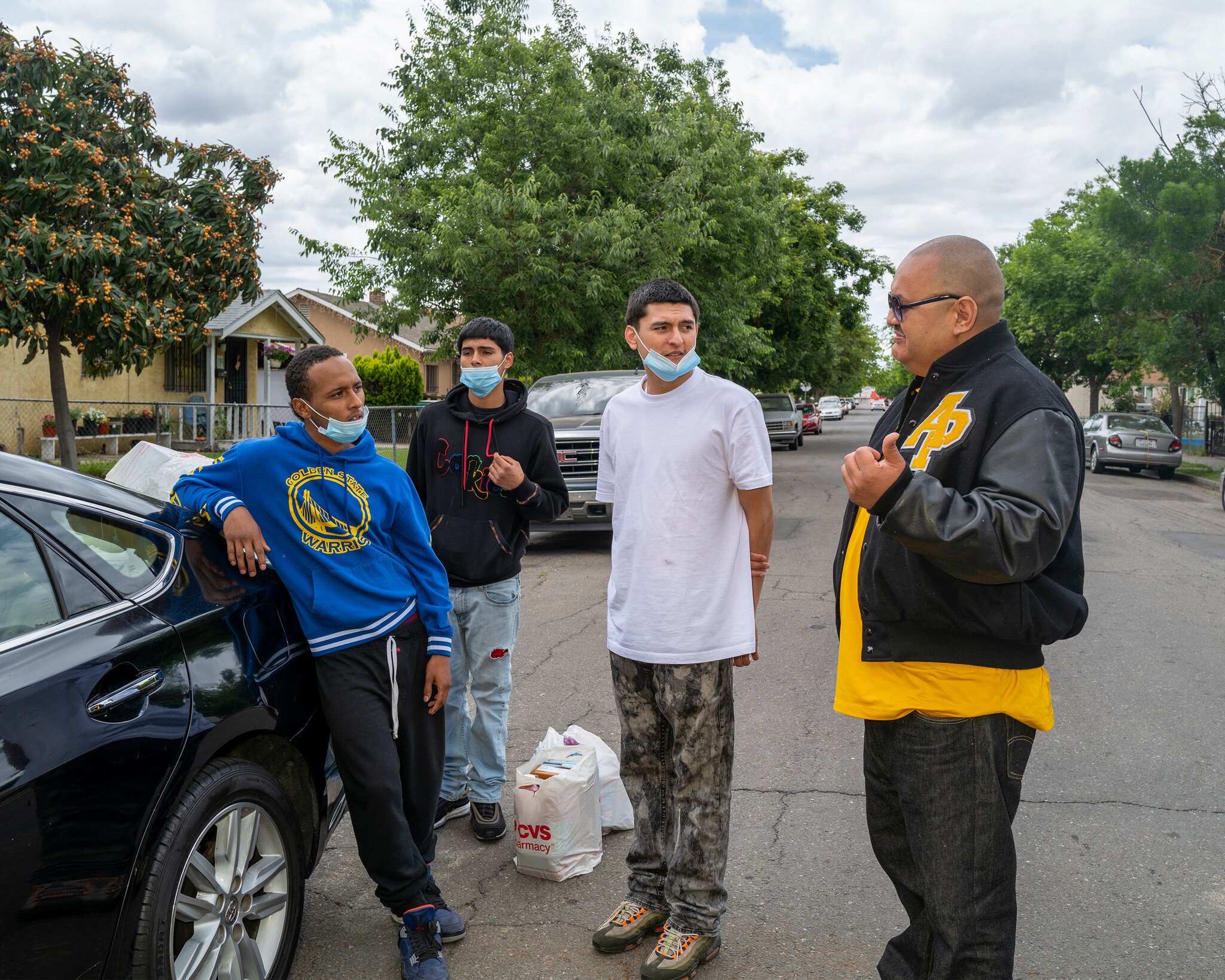

Julian Balderama, right, a “Neighborhood Change Associate,” dropping off bags of food and masks in May. Photo: Wesaam Al-Badry

July 27, 2020

Julian Balderama’s daily mission, stated starkly, is to keep a dozen boys and young men in Stockton alive and out of jail.

His official job title is “Neighborhood Change Associate” for a violence-prevention program called Advance Peace. But on the streets, Mr. Balderama is what is known as an “interrupter” — he defuses conflict. Through constant home visits, sometimes bearing takeout meals, he shows his 12 mentees how to steer clear of crime and violence, and nudges them toward schools and jobs. “These guys,” he said, “have been let down so many times in their lives.”

Mr. Balderama works with boys as young as 15 and men as old as 40, all of them either Black or Latino. At the start of the year, his biggest worry was how to keep his mentees out of the gunfire that erupts with terrifying frequency in Stockton, his hometown. But with the pandemic, and then the eruption of protests in response to the killing of George Floyd, Mr. Balderama’s work has become all the more challenging.

Now his daily rounds include offering advice on how to avoid catching the coronavirus, while also navigating how he, as a Mexican-American, can approach the complex subject of police brutality with his Black mentees.

“When the looting and rioting was happening, I did not tell them to not do that,” Mr. Balderama said. “How could I? The anger and the frustration and the ‘I’ve had enough.’ I could push somebody away like that.”

“I just said: ‘Listen, we both know what’s going on. I’m not going to tell you what to do and what not to do. But the decisions you make, you make sure they’re based on what you’re passionate about. If you’re going to do something, make sure you understand there’s consequences to your actions.’”

The multiplying risks underscore how in low-income places like Stockton, Covid-19 and the issue of police brutality have intertwined with the existing problems of gun violence and unemployment to create fresh ways of ensnaring young Black and Latino men.

Standing against these threats in Stockton are a handful of “interrupters” like Mr. Balderama and a few modestly funded city and county social service programs.

Stockton sits in the vast agricultural flatlands of central California, about 80 miles east of San Francisco. It is a working-class community that fell into steep decline after the Great Recession. A universal basic income project, investments in its downtown, and the election of its youngest and first Black mayor have generated optimism in the city. But violence remains a challenge. A 2018 F.B.I. report found that Stockton’s violent crime rate was the highest of 70 California cities with more than 100,000 residents. “A lot of folks in our community were in a crisis before the coronavirus crisis,” Michael Tubbs, Stockton’s mayor, said.

Mr. Balderama’s credibility with his fellows comes from his own difficult past. He was first incarcerated at 15, a few months before his older brother was shot and killed. In 2016, Mr. Balderama was sentenced to state prison on drug charges. He served 27 months. “You can’t talk to somebody about struggling if you’ve never struggled,” he said. “You can’t talk to somebody about starving if you’ve never starved.”

But with Covid-19, Mr. Balderama faces a tricky problem. Across the country, neighborhoods like the ones he visits grapple with a layered history of economic instability and institutional racism. One consequence of that history is inadequate access to decent medical care. Another is distrust of government, which helps misinformation about the pandemic spread quickly.

California’s surgeon general, Dr. Nadine Burke Harris, has specifically warned against rumors that endanger marginalized populations, particularly “in our communities of color, in our tribal communities, and other communities” that official information may not reach.

This is what Mr. Balderama now contends with in a region where Latinos and African-Americans account for 44 percent of Covid-19 deaths. The first stop during Mr. Balderema’s rounds is always Cesar Zuniga, 17, who would skip school and stay up all night with his brother to guard their home from gunmen who sometimes target them after dark.

Mr. Zuniga is the kind of young man who gives Mr. Balderama fits of worry. During their conversations he learned Mr. Zuniga shrugged off the coronavirus memes popping up on his social media, believing the virus was a distant threat that wouldn’t reach California and would never touch him. He refused to wear a mask.

Only after encouragement from Mr. Balderama did that begin to change. Mr. Zuniga also took a job in the local grape fields and saw all the workers wearing masks. And it really sank in after a close family member fell sick.

Before leaving Mr. Zuniga’s house to continue his rounds, Mr. Balderama reminded him he may hear President Trump is trying to roll back shelter-in-place orders. Even if that happens, he warned, you need to stay inside as much as possible. This virus is real, he repeated. All day, he ended every visit with that same message.

Another of Mr. Balderama’s mentees, a man who goes by the name Curly, believed the virus was a lie. “We thought it was people just getting colds,” he said. “I thought it was all fake.” Part of the reason he didn’t believe it, he said, was because he didn’t know anyone who was sick. Mr. Balderama urged him to take the virus seriously. Curly listened, all the more so after his girlfriend’s grandmother died from it.

Mr. Balderama said that although he avoided street protests in the past, and never would have encouraged his mentees to participate, he admits that his experience working in Advance Peace has changed him. “I was never really as passionate and emotionally affected by the way the African-American community was treated,” he said. “But a lot of people I met through this work — all these people who have affected my life in a positive way — they are Black people.”

In recent weeks Mr. Balderama has attended protests over the killing of Mr. Floyd, as have some of his mentees, although not with him. And while he advises his mentees, as always, to stay out of trouble, he also understands how vital this moment is to them. “I don’t believe any non-Black person should tell a Black person what to do in this time,” he said. “I don’t want to tell them don’t go out there, because maybe that’s all they have left.”