In Norman Rockwell country, everyone votes by mail

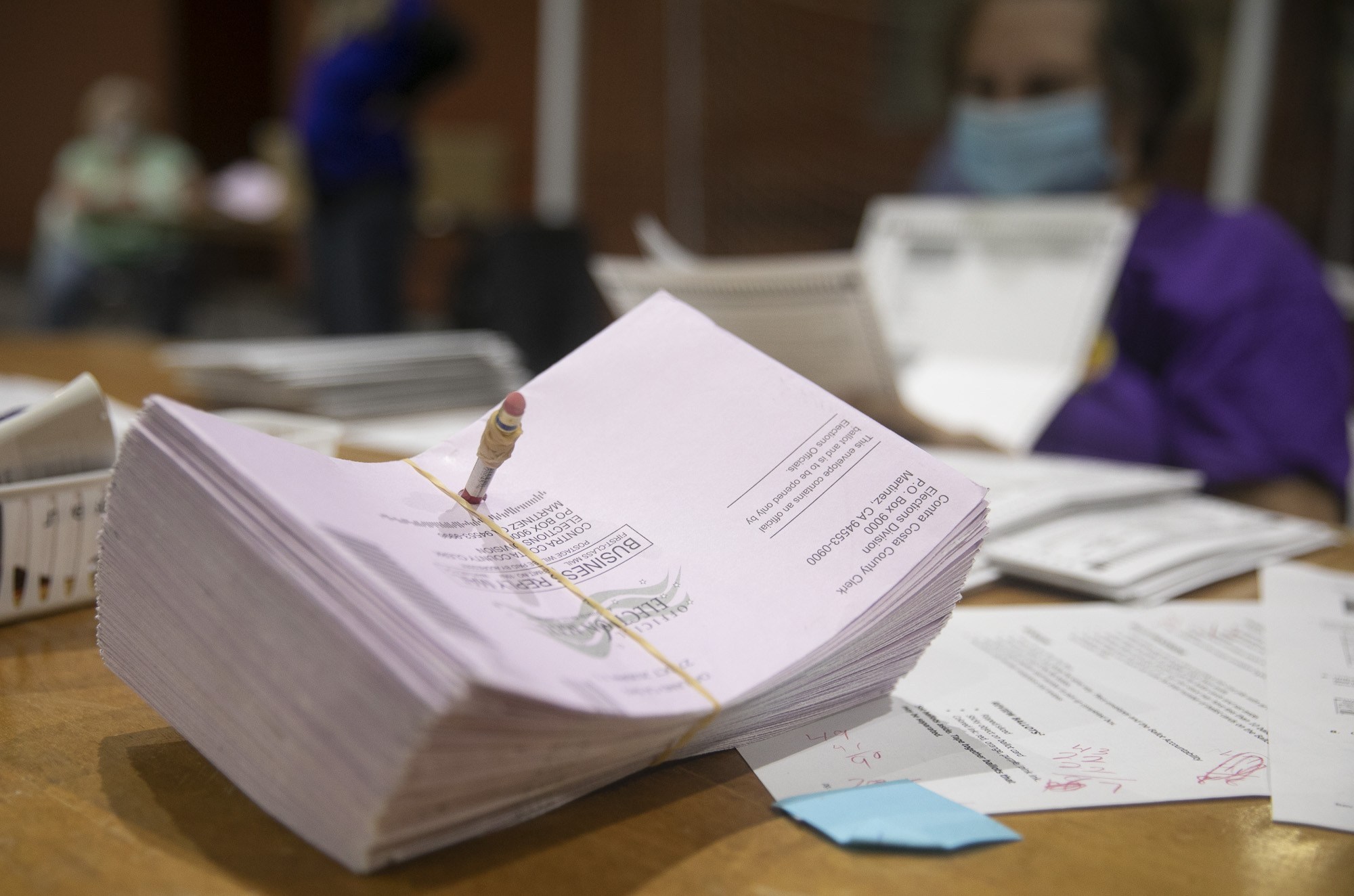

A stack of mail-in ballots on a table at a ballot extraction facility in Martinez on Oct. 31, 2020. By Halloween, Contra Costa County had already received more ballots than the total number in the March primary. Photo by Anne Wernikoff for CalMatters

NOVEMBER 2, 2020

As of Sunday night, 70 percent of voters in Plumas County had returned their ballots. The figures were similarly high in Alpine and Sierra Counties, hovering near 65 percent and dwarfing the statewide average of 49 percent.

What do Plumas, Alpine and Sierra have in common? These three counties — all rural, sparsely populated and tucked into the forested, mountainous and lush landscapes around Nevada’s elbow — are the only three counties in California that have done for years what much of the state is attempting for the first time just this year: They conduct their elections entirely by mail.

Marin County, where polling places remain open, is the only county following a traditional voting model that’s joined the ranks of voter turnout achieved by Plumas, Alpine and Sierra.

Alpine County, in the late 1980s, was the first to convert from an in-person voting model, according to County Clerk Teola Tremayne. Tremayne attributes the consistently high participation of the county’s voters, who skew elderly, white and, for the most part, equal parts Democrat and Republican with an increasing number indicating no-party-preference, to the ease of the vote-by-mail process.

“Most people enjoy voting by mail here,” said Tremayne. “This is a whole community of voters that want their voice heard.”

Tom Sweeney, who moved to Alpine County from Los Angeles to retire 20 years ago, prefers voting in Alpine. “Down there we had to go to the polls. We had to fool around and stand in line. But here they send [your ballot] to you. You fill it out in your own time sitting at your own table,” he said. “We got a real efficient system.”

Plumas Registrar of Voters Kathy Williams attributes consistently high turnout in her county to the effort her small team has put into educating voters and answering their questions about the mail-in model. When ballots have arrived at her office unsigned, she’s hopped on the phone and invited voters to drop by her office with a signature. “We know a lot of our voters personally,” she said.

Williams, who has observed more than one hundred elections in her 33 years in Plumas’s elections office, said that the last time anyone in her county voted at a polling place was in 2014. At that point, 75 percent of the registered voters in Plumas, located far from the county seat, were requesting permanent vote-by-mail ballots.

Switching over permanently just made good math. Under California’s elections code, when there are fewer than 250 registered voters in a single precinct, that precinct loses its polling place and county officials may mail ballots to its residents. Plumas County spent years consolidating its 194 tiny precincts to ensure there were enough people to qualify for an in-person voting option, but that came with a cost. The more precincts they consolidated, the farther some voters had to drive to cast ballots on election day.

Williams said most voters embraced the idea of voting by mail when the switch was finalized in 2016. She did, however, get some complaints. “I’m going to miss going to my polling place,” she recalled hearing from older voters. “They always had a potluck, or they would have donuts, and we could see our friends.

“We’re kind of Norman Rockwell here,” she said.

Voting by mail makes sense for voters who are enthusiastic and scattered across large geographic regions, said Heather Foster, the election official in Sierra County, which moved away from in-person voting entirely in 2004.

David Kimball, Professor of Political Science at the University of Missouri in St. Louis, said it’s uncertain whether entirely vote-by-mail elections could be sustainable for all of California. Much will depend on what happens after Election Day, he said, on whether mailed ballots arrive on time, and whether the ones that arrive late are counted or rejected.

“If we see relatively high rates of that happening, then I think appetites for voting by mail may diminish,” Kimball said. “We’ll see how things go.”

Robin Estrin is a reporter at UC Berkeley’s Graduate School of Journalism.

This coverage is made possible through Votebeat, a nonpartisan reporting project covering local election integrity and voting access. In California, CalMatters is hosting the collaboration with the Fresno Bee, the Long Beach Post and the UC Graduate School of Journalism.