An Interview With the Health Officer for Santa Cruz

Dr. Gail Newel has taken the heat as Santa Cruz went from being one of the safest coastal counties in the state to the site of a recent surge.

Aug. 10, 2020

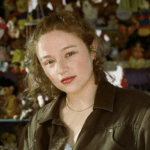

Dr. Gail Newel, health officer for Santa Cruz County, in front of the Santa Cruz Beach Boardwalk in July. The beach, which had been closed to prevent the spread of the coronavirus, has now reopened. Photo: Stephanie Penn

SANTA CRUZ — On a Sunday in mid-July, Dr. Gail Newel tried to take a “Covid Sabbath.” Dr. Newel, the Santa Cruz County health officer, put away her laptop, ignoring the hundreds of emails piling up. Instead, she meditated, played piano and spent time with her family — including her wife, an OB-GYN, and their adult daughter.

The peace didn’t last. Before dinner, Dr. Newel’s phone buzzed, summoning her to a conference call. She and other county health officers were told that Gov. Gavin Newsom was “dimming the switch” on the state’s long-awaited reopening. All bars and dine-in restaurants would shutter again. Counties on the state’s watch list would have further closures. Two weeks later, when Santa Cruz landed on that list, Dr. Newel would have to explain the whiplash to an increasingly frustrated public.

In the nearly five months since shelter-in-place orders began, Dr. Newel has taken the heat as Santa Cruz went from being one of the safest coastal counties in the state to the site of a recent surge. As the rate of infection has grown, she’s endured a torrent of abuse and threats. More and more, she is questioning her ability to curb the spread of Covid-19 with a state leadership that is sometimes inconsistent and a population that, she said with exasperation, is increasingly “not willing to be governed.”

She’s not alone. Public health officers, often messengers of bad news, have faced harassment and mistrust while communicating California’s alarming downturn to an increasingly polarized public. At least seven health officials in the state have resigned or retired since April. Dr. Newel has stayed the course so far, but her experience provides a window into the difficulty of managing a community’s health in a time of unprecedented stress and public unrest.

In May 2019, when Dr. Newel accepted the health officer job, she looked forward to serving the community in which she planned to spend the rest of her life. Dr. Newel, 63, had already retired once, in 2012, from a 14-year private practice as an OB-GYN. She had worked in the past in public health. But nothing could have prepared her to be hurled into the path of a pandemic.

At first, the way seemed clear. Dr. Newel declared a state of emergency on March 4. Two weeks later, she joined Bay Area health officers in rolling out the nation’s first shelter-in-place order. By the end of April, she’d closed indoor restaurants, prohibited gatherings and mandated face coverings. Santa Cruz stood as a model of preparedness; only 132 people in the county of a quarter-million had tested positive for Covid-19.

With summer tourism looming, she acted preemptively, signing an order in late April that closed beaches from 11 a.m. to 5 p.m. daily. (Surfers were allowed to head directly into the water.) At first, it worked. Law enforcement patrolled the shoreline in A.T.V.s and pickup trucks, issuing few citations, according to Bernie Escalante, the deputy chief of police. “Early on, the mind-set was very different,” he said. “There was a lot more willingness to cooperate.”

Soon, that changed. In May, Santa Cruzans flooded Dr. Newel’s inbox and voice mail. Control freak, they called her. Nazi. Power mongerer. Freedom trampler. Dr. Newel read and listened to every message. “Those are voices from the community,” she said. During a public hearing, a man moved toward her so aggressively that the county administrative officer evacuated the room. After that, the sheriff asked Dr. Newel to stop attending in-person meetings. “He didn’t feel it was possible to ensure my physical safety.”

Then came June. After George Floyd’s death, protesters gathered outside the police station. Others stormed the beaches. On June 6, a man alleged to be an anti-government extremist ambushed and killed a 38-year-old sheriff’s deputy in Boulder Creek, a mountain town to the north. More than a thousand people stood shoulder-to-shoulder at the deputy’s vigil — many without masks. Officers, spread thin, needed to triage. “We no longer had the bandwidth to go enforce an ordinance down on the beach,” Mr. Escalante said.

Dr. Newel began to think differently about what she was asking the police to enforce. What if an officer asked someone to get off the sand, and that person didn’t comply? She imagined a scenario where that officer might physically drag the person to a police car. “The optics of trying to enforce a beach closure became impossible,” she said.

Further complicating matters, on June 12, Mr. Newsom reopened hotels to tourism without lifting the shelter-in-place order. The following weekend, flouting Dr. Newel’s closure order, some 55,000 people filled the three-quarter-mile stretch of sand on Santa Cruz’s main beaches. At a news conference on June 25, she announced a spike in Covid-19 cases so drastic the county redesigned its online epidemiologic graph. “It has become impossible for law enforcement to continue to enforce that closure,” she said. “People are not willing to be governed anymore.”

The statement reverberated in the blue state. More angry messages ensued, uglier than before. Murderer, one wrote. Our deaths will be on your hands. Another read: If any of my family members or friends die, I’m coming for you.

Dr. Newel is no stranger to crises. She beat cancer in 2010, and lost her eldest son to an opioid overdose in 2016. Weeks ago, her aunt died after catching Covid-19 in an Ohio nursing home. Though she admitted to “feeling weary,” she said, she intends to stick it out. “I feel like I’m the right person in the right place at the right time to do this job,” she said, standing near the Santa Cruz Beach Boardwalk in late July.

Since then, the situation has grown increasingly dire. Santa Cruz County recently recorded more cases in one week than in all of April and May combined. More than 20 outbreaks are being tracked across the county, including outbreaks in four skilled nursing facilities and a homeless shelter. The county expanded the number of agencies empowered to enforce local and state health orders — but not in time to keep Santa Cruz off the governor’s watch list. On July 28, the county’s indoor gyms, hair salons and places of worship were once again forced to close.

This time, though, Dr. Newel didn’t announce the closures with a local health order. She defaulted to the state health department. It wasn’t that she was afraid of the inevitable backlash, she insisted. She just thought that if she issued the order herself, the outcome would be insignificant.

“I don’t think that there’s really much that the public will listen to in terms of local health officer orders,” she said. “They’re just not willing to do more than they’re already doing.”