Strange Bacteria Are Attacking California’s Trout Supply

When an infection was detected at a hatchery, officials, already under statewide shelter-in-place orders, moved to institute a lockdown of their own.

Sept. 29, 2020

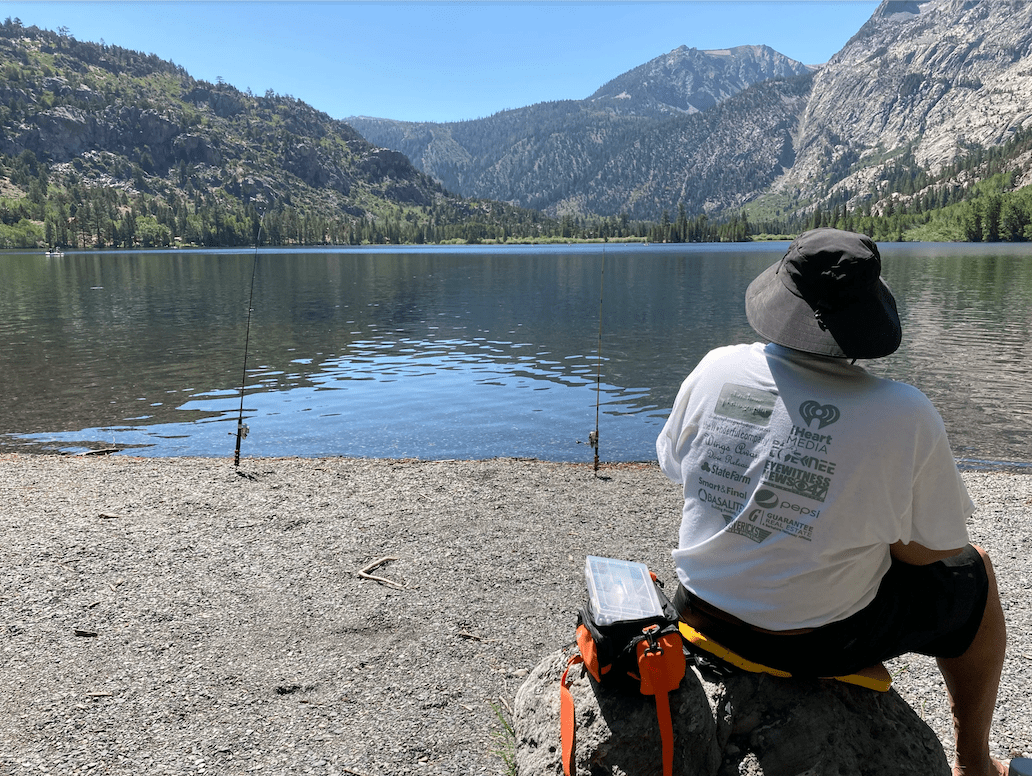

Gary Martinez fishing for trout at Silver Lake, on the June Lake Loop in the Sierra Nevada. Photo: Will McCarthy

JUNE LAKE, Calif. — On a Friday in late July, Tamara Jimenez waded into one of the many glimmering lakes dotting the Eastern Sierra. Behind her, on a small beach, her grandson filled a plastic bucket with sand.

“It just feels safer out here, like we’re away from it all,” said Ms. Jimenez, who’d traveled from her home in Orange County.

Surrounded by snow-capped peaks, aspens and avalanche scars, Ms. Jimenez felt the anxiety of the previous four months fade away.

Suddenly, she let out a startled shout. Beside her, bloated and nose up in the water, floated a dead fish.

When Jay Rowan learned in late April that trout in California hatcheries were exhibiting strange symptoms, he had been the hatchery production manager for California’s Department of Fish and Wildlife for less than a month. Already forced to rejigger operations after the coronavirus lockdowns, Mr. Rowan began to worry that a second crisis was on the way.

The employees at the Mojave River State Fish Hatchery noticed the trout were developing strange bubbles under their skin. Eyes bulged. Abdomens swelled. At first glance, the symptoms pointed to gas bubble disease, a condition that’s relatively common in hatcheries. Still, they proved odd enough that the state’s senior fish pathologist, Mark Adkison, sent a pathologist to run tests. Within a week, they had their answer: lactococcus garvieae, a rare bacterial infection. It was the first time the bacteria had ever been found in California.

As Mr. Rowan and his team were under statewide shelter-in-place orders, they moved to institute a lockdown of their own. The Mojave River hatchery, which holds about 860,000 rainbow trout, provides fish for most of the waterways in Southern California. Most fish on site had already been affected. If this bacteria somehow spread to other hatcheries, or spread in the wild, the reverberations could be devastating. It seemed surreal — a pandemic within a pandemic — but on May 4 the state quarantined the entire hatchery.

“It rarely, rarely comes to that,” Mr. Rowan said.

A dead trout in Lake Sabrina, in the Sierra Nevada. Photo: Will McCarthy

The wild rivers and lakes of California are not entirely wild. Each year, as many as 50 million trout are planted in the state’s waterways. A fish caught on a multiday backpacking adventure could easily have been raised in a hatchery outside of Los Angeles. In the Sierra Nevada, less than 1 percent of large lakes would naturally host trout. Now, thanks to a century of fish stocking, over 60 percent do.

Earlier frontiersmen, miners and cattle drivers started planting trout in fish-less California waters as early as the late 1800s. Men would travel into the high country on horseback, lugging trout in 40-pound milk jugs to stock mountain lakes.

Sporting groups followed, including the Sierra Club and, ultimately, the California Department of Fish and Wildlife in the late 1920s. As technology improved, fish brought in by horseback gave way to trucks and, in some cases, low-flying aircraft.

Hatcheries provided a natural solution. Fishing licenses would fund the hatcheries, and fishermen would get their trout. To meet those demands, hatcheries try to produce as many fish as possible, which means at most facilities you’ll find thousands of fish swimming in densely packed concrete or aluminum channels known as raceways.

But those close quarters often lead to illnesses. Lactococcus garvieae actually started at a Spanish trout hatchery in 1988. From there, the bacteria bounced around the world — Italy, South Africa — until arriving in the United States in the past decade. To date, only three other areas in the country have been hit with the bacteria, all hundreds or thousands of miles away from Mojave River. No one knows how it made it to a remote trout hatchery in California.

What they do know is that, no matter where the bacteria arrived, no one has been able to control it.

After making the decision to quarantine, Mr. Rowan and his colleagues looked to see if they could divert fish from other hatcheries to fulfill their stocking obligations. The natural choices were two hatcheries in the Owens River valley — Fish Springs and Black Rock — which hold about two million trout combined. Coincidentally, the hatcheries were conducting their annual test for viruses and infections. On June 25, the results came back. Positive for lactococcus garvieae.

State officials quarantined the two hatcheries and scrambled to determine the extent of the outbreak. At Mojave River, more than 50,000 trout had already died from the infection. Even more disturbing, most of the fish were asymptomatic.

In many counties, especially those straddling the Sierra Nevada, tourism drives the economy. Fishing is a huge part of that. According to Mono County’s Tourism and Economic Development office, tourists bring in more than $600 million every year, and over 40 percent of visitors come to fish. With Covid-19 restrictions locking down most indoor gatherings, outdoor recreation is booming. More people want to go fishing than ever. But the three affected hatcheries supply fish for dozens of creeks, rivers and lakes — essentially the entire Eastern Sierra region. Soon, the fish would be disappearing.

An hour north of Fish Springs Hatchery, on the June Lake Loop, it’s hard to tell a burgeoning crisis is at hand. Locals say visitors still seem to be pulling out six-pound trout fairly frequently. Part of that is because businesses have bought trout from out of state to help supplement their supply. Ashley Maisano, the manager of the Gull Lake Marina, said she knew it’s not sustainable, but it’s hard to focus on the issue.

“We have so much else to worry about right now,” Ms. Maisano said.

Here, every campground is full. “No vacancy” signs light up the doors of motels and resorts. Fauster Madariaga, a guide for a local outfitting company, says it’s busier than he’s ever seen it. Without the extra fish from the state Department of Fish and Wildlife, he says whatever trout remain will go quickly. Mr. Madariaga used to work in a hatchery, so he knows bacterial outbreaks aren’t terribly uncommon. But the timing of this one, and the severity? “It’s strange,” he said. “It’s just strange.”

By July 21, it became clear that the hatcheries couldn’t contain the outbreak. State wildlife officials had never seen this bacteria in California. Typical treatments proved useless. Probiotic feed meant to boost fish immune systems didn’t fare any better. The only options remaining were to watch the fish die slowly in their raceways or to euthanize them. All three million of them.

The decision proved painful. Mr. Rowan and his team are in many ways the closest to the fish. They’re the ones who care for them and watch them grow. Every day, there is genuine excitement at the hatchery, exclamations of “Look at these guys!” and “They’re doing amazing!” Killing three million of anything takes its toll.

“We got into this line of work because we love fish,” Mr. Rowan said. “It sucks.”

On July 29, state officials started the euthanization process, exposing groups of trout to high concentrations of carbon dioxide. They’re now working to completely empty and disinfect all of the raceways, and Mr. Rowan has hopes for a vaccination program down the line. But even then, it’s not clear the story will be over.

There’s a good chance all this effort came too late. Since many of the fish are asymptomatic, it’s probable that long before the lactococcus garvieae test came back positive, infected fish were being released into the wild. And so slowly, silently, the bacteria may keep spreading. And faster than anyone expected, the problem we thought was in our grasp might wriggle free, and slip away.