How Poetry Helps Dementia Caregivers Find Shelter from the Storm

by Holly McDede. This story was originally published on May 16 by KQED, where you can listen to the audio story.

Caring for loved ones with Alzheimer’s or dementia is often stressful and isolating. For caregivers in a Sacramento poetry group, led by writer Frances Kakugawa, self-expression helps channel emotion and find meaning in dementia care. (Gina Castro/KQED)

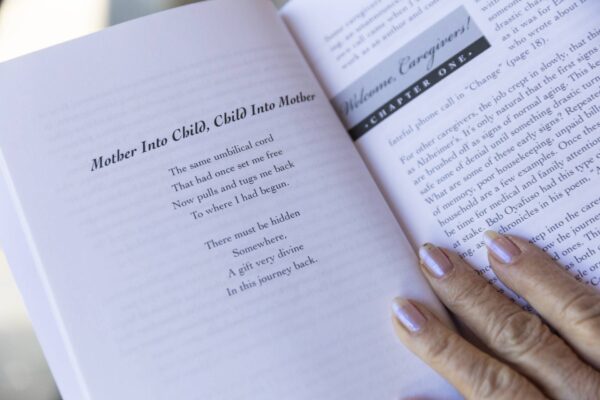

Frances Kakugawa is a firm believer that the act of caring for another human being can inspire poetry.

She knows this from experience, having cared for her mother, Matsue, who was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s in the 1990s.

Panicked that she would forget how to write her own name, Matsue penned her signature again and again and again in notebooks, Kakugawa recounted to a group of older adults at a Sacramento community center last October.

During the event, Kakugawa read from her poem, “Five Notebooks.”

Five notebooks, one hundred sheets,

Two hundred pages, twenty two lines per page.

Twenty two thousand Matsue Kakugawa.

Twenty two thousand attempts

To save herself from the thief

Who was stealing her name.

The poem “Mother Into Child, Child Into Mother,” which was the first poem Frances Kakugawa wrote about being her mother’s caregiver on Oct. 29, 2024. (Gina Castro/KQED)

Poetry helped Kakugawa take control of the painful experience of watching her mother’s cognitive abilities decline. With pen and paper, she transformed caregiving into something profound, while preserving her mother’s dignity.

“In the middle of chaos, writing poetry helped me make sense of what was going on,” Kakugawa said.

In the decades since her mother was diagnosed, Kakugawa has continued inspiring other caregivers to write poetry. For about 20 years, she’s run a poetry group in Sacramento for caregivers. She helps caregivers write poetry during monthly sessions and during lectures on elder care.

Kakugawa believes caregivers need spaces to express themselves. The role is often all-consuming, leaving people isolated, exhausted and with little time to focus on themselves.

“They’re able to process that through poetry, and become the kind of caregiver that is needed,” Kakugawa said.

Nearly 1.4 million unpaid caregivers in California are providing care for people with Alzheimer’s disease or dementia, according to the Alzheimer’s Association. And the share of older adults in the state is growing, with the Public Policy Institute of California projecting almost one-quarter of Californians to be age 65 or older by 2040. That means many more people caring for older adults may be looking for avenues to relieve stress and share their experiences.

Studies have documented the positive impact of poetry on emotional well-being, but research examining whether writing poetry helps caregivers specifically is limited. A 2011 clinical trial tested the effectiveness of writing poetry for family caregivers of people with dementia. The caregivers saw a range of benefits to writing poems, like a sense of pride, catharsis and greater acceptance of their loved ones and their illnesses. .

One example described in the trial was a woman who had been irritated by the constant laughter of her spouse. After writing a poem, “she realized that his laugh was the only sound left to her husband; suddenly, it became something to hold onto and to preserve.”

‘Caregiver Confidential’

At his home in Sacramento, Ross Powers flipped through a manuscript of poems he wrote during Kakugawa’s poetry group. He’s calling the manuscript “Caregiver Confidential.”

The poems are about caregiving for his late wife, Michela, who died in 2022. Michela had been diagnosed with progressive supranuclear palsy, a condition that causes dementia and problems with movement.

Ross Powers’ home decorated with artwork made by his late wife, Michela Maiden, in Sacramento on Oct. 29, 2024. (Gina Castro/KQED)

Her artwork fills the walls of his living room and her presence is everywhere.

He and Michela started dating in the 1980s. She was clever, funny and naturally curious, knowing the right questions to ask to keep conversations flowing. She liked to entertain those around her.

As Michela’s condition worsened, she lost the ability to read or write. She depended on her husband for everything.

Powers tried joining a support group, but the mood was too dark for him. Then he learned about Kakugawa’s poetry group, and that changed everything.

“These were people who were willing to talk, not just in an ordinary conversation, but they were willing to try and squeeze their emotions into some other form,” Powers said. “It might be an exaggeration to say it saved my life, but it saved some part of my sanity. It gave me a place to stand.”

Writing poetry helped him process this massive and confusing responsibility of caring for his wife. She needed him, and he would be there for her.

“Being of service to her was probably the great privilege of my life,” he said.

Left: Ross Powers speaks about his experience as a dementia caregiver for his late wife, Michela Maiden, at his home in Sacramento on Oct. 29, 2024. Right: Ross Powers holds a photo of his late wife, Michela Maiden, who was diagnosed with a form of dementia, at their home in Sacramento on Oct. 29, 2024. Ross Powers was his wife’s caregiver for 3 years. Ross now attends Frances Kakugawa’s poetry support group for dementia caregivers. (Gina Castro/KQED)

In his poem “Nursing,” Powers writes:

place an arm around shoulders

lean close, study her eyes

for signs of their meaning

slice, dice, crush, blend

something she can swallow

bathe her, dress her

prep the meds, liquids, liquids

always the liquids…

Oh, call it nursing, so what?

call it care-giving or compassion

call it love if you want to

‘Am I the caregiver or the receiver?’

Poems written by the caregivers also document a fleeting experience in time, memorializing the stories of the caregivers.

Last fall, Brenda Sue Pignata lost her husband, Frank.

They were both math teachers. When they met, Frank was the assistant headmaster at Sacramento Country Day School, and Pignata taught in Stockton. He asked her to dance during a math conference. He loved airplanes, and on one of their first dates, he flew her around in a little airplane.

During their 40-plus-year marriage, the dancing continued with disco lessons, even after the craze was popular. They lived together in the unincorporated community of Rescue, Calif., calling it their “little piece of heaven.”

In an interview last spring, Pignata said she began noticing signs Frank’s health was declining around 2007. Her husband had always been a gentle soul, she said, but he started becoming easily frustrated as his short-term memory declined. The family rallied around him, though “nobody ever used the word dementia, nobody ever used the word caregiver,” Pignata said.

Gardening and journaling became her refuge. Pignata said Frank, who needed the comfort of knowing exactly where she was, would sit on the deck of their home and watch while she gardened. He continued to write her love letters and leave little notes for her to find.

Just months after her husband, Pignata, also died suddenly.

At Pignata’s home in Rescue, her son Mike Smith read poems his mother wrote about caregiving for the first time. He worried his mother was so consumed with Frank that she neglected herself.

But writing poems about caregiving seemed to lift a weight off his mother’s shoulders. And now he has his mother’s poetry to read.

“There is so much of her in this house. Everything I look at reminds me of her — and of him,” Smith said. “She has so much writing for me to read and learn what was going on in her mind.”

Pignata was working on a book, “Dancing with Mr. P: Disco to Dementia,” that her son hopes to finish someday.

One of Pignata’s poems is about how she grew to appreciate simple moments with Frank. It’s called “Am I the caregiver or the care receiver?”

“I know she learned so much about caring for dementia patients, and dealing with the feelings of guilt, sadness, sorrow and grief,” Smith said. “And I guarantee you that other people are going to find that valuable. I just need to be able to get it out there.”

The force holding the poets together

For Diane Woodruff, a caregiver from an earlier cohort, poetry helped express her gratitude to Kakugawa after the poetry teacher danced hula at the Alzheimer’s facility where her mother stayed.

In the piece, Woodruff described how Kakugawa transformed into a hula goddess.

I learned a valuable lesson from my poetry teacher and the Hawaiian hula goddess that day

It is important to continue to create fun in the darkest times and places

Laughter is the medicine of the Gods

It helps us get through the toughest times

Frances Kakugawa interacts with her mall friends at the Arden Fair in Sacramento on Oct. 29, 2024. The group walks around the mall almost daily every morning. (Gina Castro/KQED)

Hearing so many poems about pain and redemption, compassion and frustration and love over the years has inspired Kakugawa, but it has also left her feeling burned out.

As caregivers gradually leave the poetry group over time, she expects it to fade away on its own.

Growing up in Hawaii, Kakugawa decided she was going to become a writer when she was six years old. She kept her poetry a secret for years and escaped to the outhouse to enjoy rare moments of privacy and read whatever she could find.

Now she shares her poetry with strangers — everyone from caregivers to older adults she meets at a shopping mall near her Sacramento home.

She’s working on a book called “The Outhouse Poet: Reflections of a Writer.”

Kakugawa expects that book to be her last. She’s ready to relax — and to take care of herself.

Reporter Holly J. McDede is a writer with the Investigative Reporting Program at the UC Berkeley Graduate School of Journalism. She covered this story through a grant from The SCAN Foundation.