Alyson Stamos and Meiying Wu

Alyson Stamos (’20) and Meiying Wu (’20) reveal how early planning and communication spared San Francisco’s Chinatown from the brunt of the COVID-19 pandemic.

In January, Meiying Wu (’20) had flown to China for Chinese New Year. Unlike previous holiday visits, she couldn’t go out to see family and friends. An epidemic had started in the country and no one was out. When she returned to San Francisco at the end of the month, she voluntarily self-quarantined for two weeks, long before the term had entered Americans’ everyday vocabulary.

The arrival of the coronavirus in the U.S. soon after brought with it a tide of xenophobia, perpetuated most notably by disparaging comments from the president about the country of origin.

This helped focus the new COVID-19 reporting of Wu’s Berkeley Journalism classmate, Alyson Stamos (’20): “What has been happening to Asian Americans across the United States and all these acts of hate?” she asked herself. Stamos was pursuing a few stories for Berkeley Journalism’s “Chronicling COVID-19” project, and had heard about a hospital in San Francisco’s Chinatown and wanted to know what was going on there. She asked a doctor whether he knew anyone there, and she was put in touch with his doctor friend at Chinese Hospital. “Within that first conversation, I immediately knew the uniqueness of the hospital,” she recalled. Despite the mounting vitriol, Chinatown appeared to have remarkably few cases. “This was definitely an area I had to dig into,” Stamos decided.

The resulting story she reported with Wu, about how coordination and swift action kept the coronavirus under control in Chinatown, ran in The New York Times in April and, three months later, was a segment on the PBS NewsHour. They reported that, led by Chinese Hospital, major Chinatown institutions began working together, leveraging their connections to China, implementing health and safety measures, and informing residents long before any American jurisdiction even contemplated a lockdown.

Proving “many people’s assumptions wrong”

“This story is important because it proves many people’s assumptions wrong,” Wu said. “When people assume Chinatown’s connections to China would put the community at higher risk to be infected with the coronavirus, the community in fact learned from China’s lessons, took early action, and has prevented an outbreak when many of its members live in cramped apartments with shared kitchens and bathrooms that made it almost impossible to quarantine.”

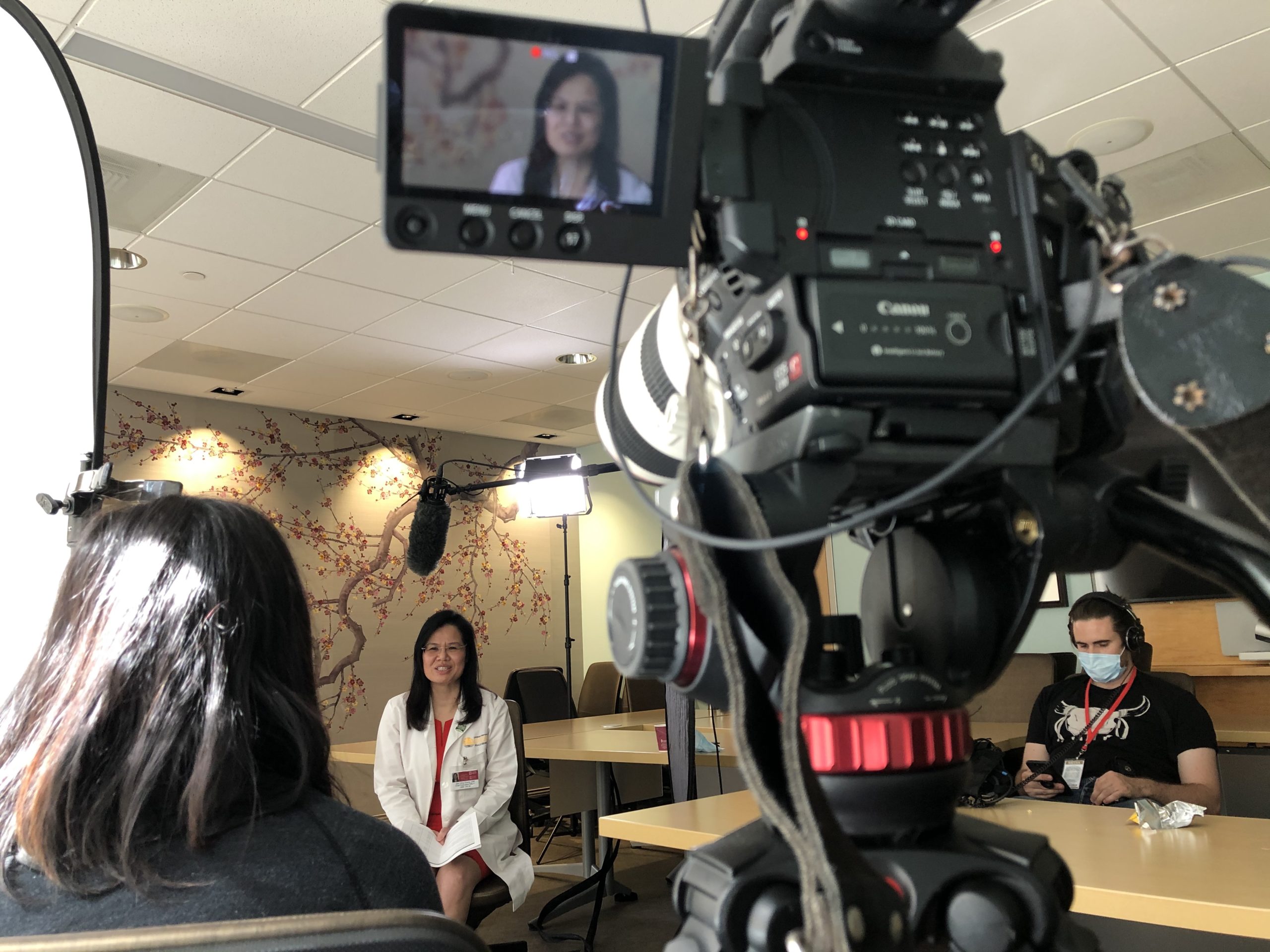

Alyson and Meiying reporting at Chinese Hospital

Wu, who studied in the multimedia track, has focused her graduate work on marginalized voices, including deaf students in India and HIV patients in China, and is starting a video internship at the Los Angeles Times in August. Stamos, who studied in the video journalism track, often covers environmental and immigration stories, particularly those in the Asian and Southeast Asian communities. She’s currently Cisco’s director of strategic executive communications.

When the pandemic struck the U.S., the Graduate School of Journalism turned into a newsroom for covering the coronavirus for a variety of publications, most closely with The New York Times, and the pair began covering the impact in San Francisco. Editing the story was Lecturer Mark Schapiro.

“Alyson has very good sources in San Francisco government and politics,” he said. As Trump was disparaging China and, implicitly, Chinese Americans, Stamos was hearing how much better Chinatown was doing than the rest of the city.

At the same time, Wu had been monitoring the city’s vibrant Chinese-language press and learning the importance of Chinese Hospital as a community institution. She listened to a Cantonese radiothon raising money for Chinese Hospital to get personal protective equipment and learned that the alumni associations of two Wuhan universities had donated. “Alyson and I then split the reporting tasks,” she said. “I talked to the alumni associations and other community members; she focused on the city’s collaboration with Chinese Hospital. Her network in San Francisco and my language skills put us in an unique position to tell this story.” They’d be on the phone with each other about the story first thing in the morning and wouldn’t call it a night until 9 p.m.

“They both did really excellent reporting,” Schapiro said.

“Alyson and Meiying did a really amazing job putting all those puzzle pieces together and then producing the story that got published in The New York Times,” said Prof. David Barstow, a former Times investigative reporter.

He and Schapiro worked with them on the text, while professors Koci Hernandez and Ken Light and The Times’ Morrigan McCarthy advised on Wu’s photography. After numerous drafts, fact-checking, and honing the narrative and framing, it was sent off to Times editors, who immediately wanted to publish it. “It went into the newspaper pretty much exactly the way we sent it,” Barstow said.

“It was the unique story, a hard-working reporting partner, and great guidance and support from Mark, [Interim Dean and Professor] Geeta [Anand], and David that made it happen,” Wu said.

“To find a reporting partner that you can work with — not only on one medium, but across multiple mediums — and at the end of it you still would work with them in a heartbeat, is incredibly rare,” Stamos said. “Not only was it just really good work, it was just really fun.”

“A very sophisticated piece of TV journalism”

A week after the April 17 publication in The Times’ “California Today” newsletter, Wu and Stamos spoke to KQED’s The Bay podcast about how Chinatown prepared for the pandemic. At the same time, The Washington Post cited The Times story in a fact-check of comments President Trump had made about Rep. Nancy Pelosi and Chinatown. Barstow said The Times story received many complimentary comments from readers who appreciated it. One of the readers was a producer at the PBS NewsHour.

Andrés Cediel, a professor of visual journalism, had PBS connections and took over guidance for the visual piece Wu and Stamos were now starting on. “Although we’ve understood the timeline of Chinese Hospital and the community’s early action and prevention, the new challenges included showing the action, which happened two months before our shoot, in our video,” Wu said. “We also had to find the right [single-room-occupancy unit], build trust, and convince the elderly residents to let us film in their 70-square-foot apartments.”

The challenges of visual storytelling were compounded by those of reporting amid a pandemic, requiring physical distancing, gloves, many sets of wireless mics, and frequently disinfecting equipment. Both of them produced the TV piece, and Wu handled the videography. The NewsHour, Wu said, didn’t ask them to edit it much after first receiving the piece.

“It was a very sophisticated piece of TV journalism,” Barstow noted of the July 15 segment.

“It was impressive to see how Alyson and Meiying transformed their print reporting into visuals, finding the right characters and moments to illustrate this important story,” Cediel said. “This meant being out filming in the middle of a pandemic — in a hospital, and in crowded living situations — and keeping themselves safe, as well as their subjects. The result was a perfect portrait of an immigrant community coming together for the benefit of all.”

The pair worked with a couple of Class of 2020 peers to produce the piece. Christian Collins recorded sound, and James Tensuan edited video.

“This story was constantly evolving,” Tensuan said. “There were maybe three or four times where Alyson and Meiying had to re-call sources to keep the COVID hospitalization numbers up to date. Then after getting those numbers, they’d have to rewrite the script and get that back to me for a new edit to deliver to the NewsHour.

“Situations like this can be incredibly frustrating and stressful, but this team made it feel completely natural,” he added. “The workflow was completely fluid and I think they set the bar for what a professional team is.”

“While I was just recording sound, providing input, and carrying gear and footage around, the story really impacted me and the people in my family,” Collins said. “It shows the unifying power that the virus had and the collaboration between two countries and a large community is something our leaders can learn from.”

To “contribute something really meaningful”

“Our desire isn’t simply to get students published — although that’s terrific,” Barstow said. “Our deeper hope is for them to actually contribute something really meaningful to the public conversation through the work they’ve been doing. And this story did exactly that. It was really interesting and new and fresh and definitely added something to our understanding and our knowledge.”

“It was such an implicit repudiation of the crazy and ill-informed and revolting characterization of the way in which Chinese-Americans were characterized by our government and continue to be to some degree,” Schapiro said. “It was also a great health story, just a great story about, What do you have to do to deal with this virus? It was a glimpse of this community that most people don’t have a glimpse into.”

Many of those lessons, however, haven’t been learned, making the story’s TV broadcast just as relevant three months after its print debut. “The pandemic isn’t over yet,” Stamos said, “and many people can still learn from Chinatown.”

Despite those explicit lessons, she added, the heart of the story is still “what happens when a community comes together and all the parts of the community are speaking to one another.”

–Sam Goldman