Credit: San Francisco Chronicle

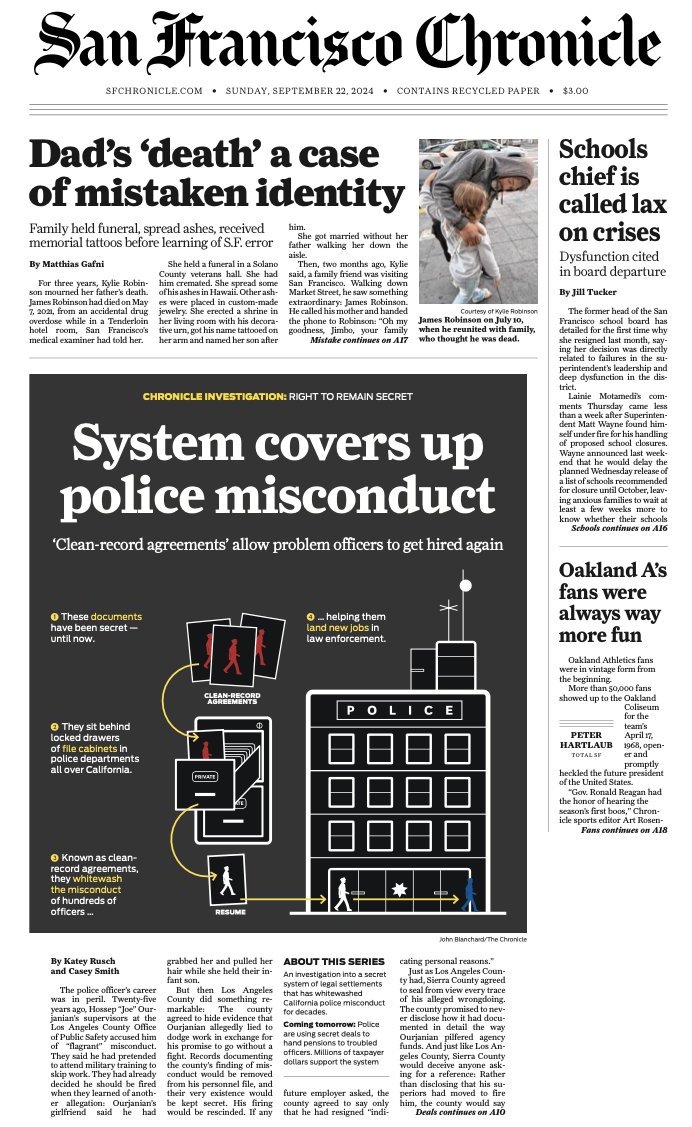

A secret system of legal settlements has concealed corruption, criminality and misconduct by law enforcement officers throughout California for decades, according to a new investigation “Right to Remain Secret” by Katey Rusch (‘20) and Casey Smith (‘20) of UC Berkeley Journalism’s Investigative Reporting Program. The investigation, published in collaboration with The San Francisco Chronicle, reveals the widespread use of so-called “clean-record agreements,” which mask problematic and even illegal police conduct — including dishonesty, sexual assault and excessive force — allowing errant officers whose careers in law enforcement are in peril to end up at new jobs with other agencies. These agreements often sit in locked filing cabinets. Rusch and Smith’s story is the first to describe how they protect and perpetuate police misconduct.

Rusch published a second story showing that in some cases, a clean-record agreement not only made it possible for troubled officers to hide misconduct but it also enabled them to qualify for a disability pension.

The Investigative Reporting Program’s Aysha Pettigrew interviews Rusch about these stories and genesis. This conversation has been edited for clarity.

___________________________________

Aysha Pettigrew: How did you start reporting about clean-record agreements?

Katey Rusch

Katey: I was working on a project [between my first and second years at UC Berkeley Journalism] with other reporters at the time about officers in California who had criminal convictions. We were reporting on a story about a police department in the middle of California that had hired a number of officers with criminal convictions and other alleged misconduct. Some of these officers had said contradictory things to what we had seen in the documents. They had received notices of termination, which basically, in the police world, means that they’ve been fired. But the officers, once we talked to them, claimed, ‘No we hadn’t been fired, we’d never been fired. Check your sources. Check with the department. Check with the state.’

[Fellow J-School student] Casey Smith, who is the co-byline on the story, had been working on another project about police departments and settlement agreements with victims of police violence. And she said, ‘Well, maybe they have some sort of legal agreement.’

I knew some of the officers had sued their department, but somewhat on a lark, I requested these agreements — specifically settlement agreements involving any lawsuits, grievances or other mediated conflicts — from the Banning Police Department, which is in the Inland Empire. I got back five agreements within the week and I was shocked to see that in fact, these agreements made sure that it looked as if the officers hadn’t been fired. In other words, the agreements said that any records related to their termination would be placed in separate files and the department would report to the state that they hadn’t been fired and that they had resigned voluntarily.

-

Casey Smith (’20)

I remember pretty vividly that Casey and I took these agreements up to [IRP Director] David [Barstow]’s office and he said,“You’ve got to see if this is happening everywhere.” So we started requesting these agreements and we started seeing the same things. That’s how it started.

Aysha: How did you learn how to file public records requests? Was that something you were doing in your previous job as a TV journalist? Was that something you learned to do here?

Katey: I had done it a little bit, but I wasn’t doing it that much. I actually learned how to do it from Tom Peele, who worked at the Bay Area News Group. He taught a class at the journalism school where he helped all of us send public records requests.

He was leading a project related to police misconduct records that were newly disclosable under state law and he taught me the basics. From there, I got really into it. I did deep dives on case law and started requesting records. I also worked with Susan Seager at UC Irvine and she was really helpful in helping me understand the basics of the CPRA [California Public Records Act] and how we could get records that were confidential, like the clean-record agreements.

Aysha: Once David Barstow advised you to ‘find out if this is happening everywhere,’ how did you start?

Katey: We initially started by filing records requests with a smattering of agencies at a bunch of different locations, to find out if it was happening in one area of the state, if it was happening in just big departments or also in small departments. Once we saw that it was something that was happening at a bunch of other law enforcement agencies, then we kept growing and growing and growing the number of requests.

Credit: San Francisco Chronicle

Aysha: Reading the stories, something that really struck me is just how many of these agreements you found and how many officers you talked to. When did you realize the scale of this reporting?

Katey: I think I realized it probably a year and a half in. It took a long time to get agencies to actually understand what we were requesting because these documents are so confidential that the records custodians — primarily city clerks and county counsel — are not even aware that they exist. The defining moment was talking to an attorney representing the L.A. County Sheriff’s Department [about] executing these agreements and how many agreements they had within the L.A. Sheriff’s [Department]. And that made me realize, “Oh, this is a thing.”

I don’t think there’s anything better I could have done with the last four years than getting to work with David [Barstow] and all of you folks at the IRP. Even in the depths of a pandemic, I woke up every day grateful that I got to do this work.

Aysha: How long did you spend on this project in total?

Katey: Four years.

One of the great things about the Investigative Reporting Program — one of the reasons I’m so happy I get to work for an organization like this — is that every single word in here reflects hours and hours of work. And we’re allowed to take the time to do that.

Katey Rusch reviews documents at the offices of the Investigative Reporting Program at UC Berkeley Journalism.

Aysha: What were some of the challenges that you faced doing this reporting?

Katey: Well, we were requesting the records during COVID. So at first, it was just getting agencies to comply with the Public Records Act during a pandemic.

After that, it was the challenge of trying to get people to speak about information that was made confidential by these agreements. Some of the people in this story are speaking out in potential violation of some of these agreements because they feel strongly that the information should be out there. That was one of the most difficult parts — finding sources who felt comfortable speaking about something that they thought they would never talk about again.

Aysha: What is the impact that this project has had so far?

Katey: There have been a few people who are under investigation by their current employers. And there have been a few people who have left jobs because of some of the questions that I have asked. That’s what I can say officially.

Aysha: What do you think are the most important things you want people to take away from these two stories?

Katey: I’d really like people to understand that there was a system at play, and that some of the results of this system are that these employment agreements can hide misconduct.

Aysha: Outside of California, how many other states allow law enforcement agencies to use clean-record agreements?

Katey: I have seen clean-record agreements in almost every state in the United States. Some of the sources I talked to in other states say they are more pervasive in places like California, where the unions are more robust, than in places like Kansas. But as far as I can tell, these agreements are pretty commonplace in law enforcement agencies across America.

Aysha: What drew you to the Investigative Reporting Program at UC Berkeley Journalism?

Katey: I was working as a TV journalist in Seattle, and I always wanted to do investigative work. And I thought that the place where I was working as a TV journalist would not allow me to do that. And I just wasn’t finding that I was doing as much work on the reporting as I was on the actual production of video and audio. I had been watching PBS Frontline and was a huge fan of now-Emeritus Professor Lowell Bergman. And I just thought, ‘Man, this is the place where I want to work.’

Aysha: In closing, what do you wish you’d known as an IRP student?

Katey: I think that as a student, and as someone coming into this, I thought, ‘The longest I could work on something is six months. I can never work on something for so long.’ I wish I would have known that it does take time…that good things take time.

But as frustrating as parts of this project were, I don’t think there’s anything better I could have done with the last four years than getting to work with David and all of you folks at the IRP. Even in the depths of a pandemic, I woke up every day grateful that I got to do this work.