The December morning was crisp and clear, a quiet Saturday in Oakland, and Thomas Peele had barely woken when he heard his cellphone chime. The text came from a photographer Peele knew, who had been up all night. It was a single expletive. Peele sent back a question mark, and the photographer replied: ‘Nine dead. Twenty-five, thirty missing. Warehouse fire.’

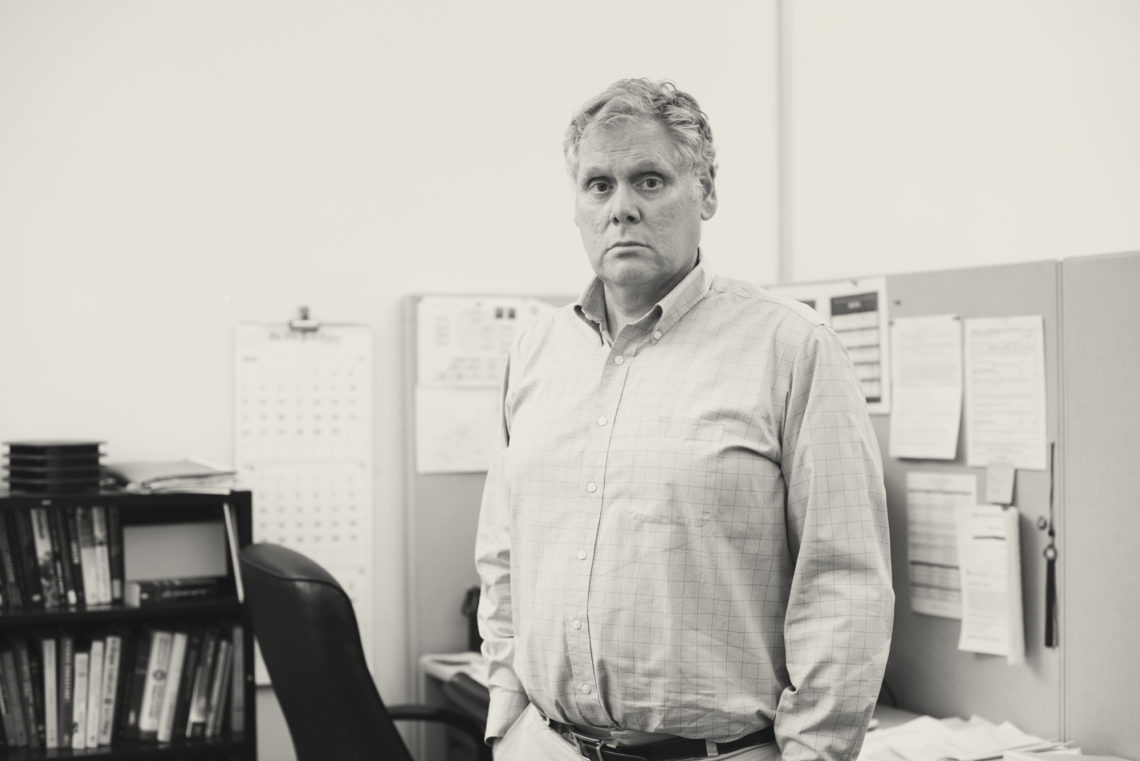

Peele didn’t hesitate. An investigative reporter for the Bay Area News Group and lecturer in public records at the UC Berkeley Graduate School of Journalism, he knew a huge story had just broken. He got dressed, and told his wife he had to go into work. He didn’t know when he’d be back.

Driving to the East Bay Times office, he turned a flurry of questions over in his head. Details about the fire were sketchy and incomplete. It would be Peele’s job to get the facts, fast, and lead an investigation into how the disaster, which would come to be known as the Ghost Ship Fire, had been able to happen. In his car on that December morning, he had no idea that the reporting he was about to do would ultimately win the Pulitzer for breaking news.

The prize was a capstone on the career of the 56-year-old reporter who has been awarded over 60 journalism honors, and routinely breaks stories on government malfeasance and corruption.

Yet, Peele began his career as a college dropout, working at a tiny free weekly newspaper in Bridgehampton, N.Y. He was a busybody reporter, photographing and working in production as well as writing news stories, and occasionally collecting gas for the paper’s printing press, which was mounted on blocks in a backroom and ran on a Ford Pinto engine.

After graduating from Long Island University with a degree in journalism, he worked as a beat reporter at various East Coast papers, reporting on municipal, state, and congressional affairs.

“I got really lucky,” Peele remembers of his time at one New Jersey paper. “They assigned me to a town where everyone was a crook.”

He reported on the town for two years, honing his investigative skills by sifting through public records and financial documents to unearth a municipal scandal in which officials stole millions. His reporting led to criminal charges being brought against 11 people; all were eventually convicted. It was the kind of work Peele knew he wanted to do, and his experience in New Jersey “gave me some degree of confidence that I could do it,” he said.

In 2000, after six years in Atlantic City (a town he describes as “one of the most corrupt cities in America”), he moved to California to work as an investigative reporter for The Contra Costa Times. His focus shifted from statewide investigations in 2007 when Chauncey Bailey, a community reporter who was looking into violence and fraud perpetrated by a shady Oakland organization, was murdered in broad daylight.

That year, Peele collaborated with many other reporters, as well as students from the Berkeley J-School, to investigate the killing and finish the work Bailey had started. “This was bigger than the murder of one weekend editor in Oakland” Peele said. “This was an assault on the First Amendment.” The Chauncey Bailey project consumed his professional energies for five years, but led to the jailing of all those involved in the murder.

Neil Henry, then dean of the Berkeley J-School, was impressed with the work students had done to help the project, and saw a gap in the School’s curriculum. He invited Peele to co-teach a class on public records. That class has continued for many years, giving first-year students a strong foundation in essential investigative skills.

Peele impresses a simple mantra on his students, known as the “document state of mind.” A good investigative reporter, he says, always looks for the record first, verifies everything they find, and knows the benefit of a diversity of documents.

This straightforward advice has guided him throughout his career, and acts as the starting point for any new investigation. So when word of the Ghost Ship Fire broke last December, his first questions were those which could be answered through public records. On his way to the East Bay Times that morning, he wanted to find out who owned the warehouse and when it was last inspected by the fire department.

His team worked 15-hour days for a week straight. Their first story went live within hours, reporting that the warehouse had been under investigation for being illegally converted. For the rest of the week, they dug into what the city knew about the Ghost Ship and what had been missed, uncovering city negligence and individual incompetence.

“This was a national story, that first week,” Peele said. “And frankly, we owned it.”

It was the team’s reporting over those first seven days that won the Pulitzer. But while there was champagne in the newsroom on the day the prize was announced, Peele and his team are acutely aware that the honor comes after a tragedy. Thirty-six people died in the Ghost Ship. The East Bay Times has contributed the prize money it has been awarded for its coverage to a fund for victims’ families.

Peele now balances his time between East Bay papers and projects at the UC Berkeley Investigative Reporting Program. “It’s a fabulous school to be associated with,” he says of the J-School, adding that, for him, the best thing about teaching at Cal is “getting a look at the future of journalism.”

“To see people really get something out of this, and see people end up at places like NPR and The Washington Post,” he said. “That’s rewarding.”

For now, he’s back on the investigative beat, focusing on stories in the central valley, and indulging in his second passion: Bruce Springsteen and the E Street Band. When Steven Van Zandt tours in San Francisco later this year, Peele will be there, racking up another in his 250-plus shows. (“I lived in New Jersey for a while for a reason,” he smiles.)

Of all the Boss’s records, Peele names as his favorite Darkness on the Edge of Town. It’s a brooding album revolving on loss and grit in the face of adversity. Rolling Stone called it a record about the rejection of despair. It is an apt choice for a reporter who has spent his career grappling with society’s darkest elements, and who works to shed light on our cities’ forgotten corners.

By Rosa Furneaux (‘18)