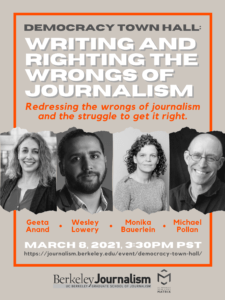

Four leading journalists discussed efforts to transform news coverage of race, social justice, agriculture and other key issues in a panel called “Writing and Righting the Wrongs of Journalism” held at UC Berkeley on March 8.

Moderated by Berkeley Journalism Dean Geeta Anand, the panel featured Monika Bauerlein, CEO of Mother Jones, America’s longest-established investigative news organization; Wesley Lowery, special projects editor at UC Berkeley’s Investigative Reporting Program and a Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist who focuses on race and criminal justice; and Michael Pollan, UC Berkeley’s Knight Professor of Science and Environmental Journalism, who has changed our perspectives about food.

The hour-long online discussion was part of UC Berkeley’s “Reimagining Democracy Town Hall Series,” which promotes participation in the democracy process. Here are some highlights, which were lightly edited for clarity:

On the importance of reporting on the “systems” in our society:

Michael Pollan: You can’t understand the way we’re eating and the obesity crisis and food safety problems … without looking at farming practice, the fact that we grow everything in monocultures; without looking at agricultural policies, the subsidies that determine what gets grown; without looking at capitalism, which only thrives when it can add value to cheap commodities. I started putting together all these pieces and I came to understand that you could explain what I came to think of as our national eating disorder by putting it together in a system. How do you make a system interesting to readers? That then became the next challenge … My editor said, “Why don’t you just tell the story of one animal?” This was an enormous breakthrough for me. I realized I could use a single animal’s lifespan as a laundry line and on that laundry line, I could hang all those different issues at the appropriate place. When we get to the feedlot, we could learn about corn and the diet. When we get to the slaughterhouse, we learn about humane practices. I learned, in the process of doing that piece, that narrative was a powerful tool to illuminate a system. And that’s really been my focus ever since. What journalists do best, but do all too seldom, is connect the dots. That’s really what we need to know about something like food. But it applies to politics also. It applies to so many things. The interests of the powers that be is to keep things separate, to keep things unconnected, as we had not connected the production of food to the consumption of food. These things can be understood as a system and narrative is the best tool to illuminate that system.

Monika Bauerlein: Mother Jones was founded and grounded in a place of values. Not necessarily partisan values, but a commitment to justice and democracy. Over the decades that has really helped our journalists get away from the false equivalence, the he-said she-said reporting that particularly in political journalism has really hampered us … I think we see that most clearly in the way race and racial injustice has been covered as a problem of individuals more so than a problem of systems … We saw that in 2015 and 2016 when the rise of white supremacists and authoritarian and anti-democratic forces were facilitated, but not entirely caused by the rise of the Trump phenomenon. A lot of political journalism was really not prepared to grapple with that because it was happening outside the parameters that defined every political story as an accurate rendition of what a Democrat says and an accurate rendition of what a Republican says, without a look at the systems in which that plays out. That was an area where at Mother Jones, we were able to double down on covering these forces, on covering this moment as a crisis in democracy … Political coverage is still not sufficiently focusing on voting rights and voter suppression as the foundation story of this political moment … The independence of being a values-grounded nonprofit news shop has allowed us to try to step into these stories more vigorously.

From top left (clockwise): Geeta Anand, Michael Pollan, Monika Bauerlein and Wesley Lowery participate in a panel discussion on “righting the wrongs of journalism.”

On rethinking objectivity in journalism:

Wesley Lowery: One of the key issues in this era of coverage around race and policing is that the vast majority of coverage has covered these stories as political stories, not as policy stories … not government accountability stories. When the police kill someone, the government kills someone. It’s not an issue upon which you are taking a survey of people’s thoughts. It is, at a fundamental level, government accountability. The burden of proof is on the government. I think that so often that disposition is missing … This is values-based journalism. The value here is that people are owed accountability from their government. They are owed answers from their government …The government killed one of its citizens. Explain why that was okay — not “citizen, explain why you didn’t deserve to be killed.” That fundamentally and structurally changes the way you approach these kinds of stories. Secondarily, it changes the rigor with which you seek answers to big questions. It should be unacceptable to everyone that we don’t know precisely how many people the government kills in a given year. What more foundational question could there be? Yet we know so little in terms of official data and official information about law enforcement.

Monika Bauerlein: The field is really grappling with the notion of objectivity and what it means. I’m going to say something personal. My father wrote his thesis on objectivity in Germany in the 1950s in the immediate aftermath of dictatorship and genocide. I remember asking him about this when I was coming up. He said that was the anchor to which we could cling as an antidote to propaganda. Journalism had existed previously as an inservant to disinformation, propaganda and genocide. Objectivity was a way to pull it out of that. A generation later, we come to a point where we recognize that the anchor is also weighing us down. We need a grounding in fairness and truth, but that objectivity specifically has been allowed to drag us into a place where we’re actually not pursuing fairness and truth, but pursuing a formal structure of what journalism looks like — the “he said, she said” structure and all that comes with it. For the future, where we want to be headed is to orient ourselves to not just be about what journalists should do, but what our audience, what the people we serve, need us to do, and what they need to function as citizens of a democracy, if we can get it is truth. What we need to exist as journalists is a democratic society that’s based on truth. These interests are intertwined. We’re no longer separate from this long arc toward more democracy and freedom.

Michael Pollan: The whole issue of values in journalism is really fraught. On certain beats, values have always been okay. From the beginning of environmental reporting, it was okay for reporters to be environmentalists, to believe in climate change, to believe that something should be done to keep the water clean and the air clean. This struck me as weird because there were so many other beats where you were not allowed to have values and let them inform you. Over time, I think that values are becoming more acceptable in journalism. I think it has something to do with the collapse of the advertising model, which supported newspapers for about a century and was kind of invented by The New York Times — they hit on this idea that if you weren’t a tool of propaganda or a tool of a political party…and you did “on one hand, on the other hand” objective journalism, you could draw a lot of advertising because advertisers didn’t want to be in the realm of conflict…As Facebook and Google hollowed out the advertising market, newspapers and magazines…had to turn to their readers and the needs of their readers, which are different from the needs of advertisers. I think that’s where we are. By and large, I think it’s a healthy development. I think it’s better that people pay for information rather than have a third party with its own interest pay for that information… I think the challenge is how far do you go in letting your reporters’ values drive your coverage. Is there a point where you fall back into that period that Monika was addressing, where everybody is so subjective and advocacy takes over, that your credibility declines? That’s a huge challenge for editing.

On public distrust of the news media:

Wesley Lowery: We have had, in the post-Watergate world, a single political party that has spent 50 years telling the American populace not to trust us. The “don’t believe the liberal media” signs showed up in the 1988 Republican convention and have been there ever since. You look at the things that President Trump said, other than literally “enemy of the people,” they were the exact same things that Newt Gingrich said, that Nixon said, that every member of the tea party said. I just can’t believe as a premise that if you have a political party that represents 30-40% of the country and it spends 50 years with its most consistent ideological talking point being the media is systematically biased against us and you cannot trust it, that that does not have a significant impact on whether such people trust us. I do worry sometimes that we’re seeking a trust that is never going to exist — if you have a subsection of the population that has been so consistently primed to never trust us and we’re bending over backwards in all these ways to try to convince them to do something they’re never going to do. It’s the girl who’s never going to take you back. No matter how many flowers you buy, it’s not happening.

The event was co-sponsored by Berkeley Journalism and the Social Science Matrix. You can watch the panel discussion in its entirety here.

By Janice Hui