Faculty, staff and reporter-graduates gather after closing ceremonies in 1976 of the Summer Program for Minority Journalists. Dean Edwin Bayley opened the graduation ceremony, culminating the first SPMJ training session conducted at the UC Berkeley Graduate School of Journalism. The program then was run by the nonprofit Institute for Journalism Education, which later was renamed the Maynard Institute in honor of the late Robert C. Maynard, a founding director and former Oakland Tribune editors and publisher. Photo by Nikki Arai. Courtesy of Frank Sotomayor.

More than 200 Black journalists studied at Berkeley Journalism during the ’70s and ’80s in a landmark summer diversity program many know nothing of. They went on to work for news organizations around the country. Some went on to win national recognition, including the Pulitzer Prize.

At a conference for newspaper executives in 1978, civil rights leader the Rev. Jesse Jackson called it a sad commentary “that the print media may be behind almost every other major institution in this society … in accepting Blacks.”

Jackson was right about print, and the broadcast news industry at the time was even worse.

But as Jackson uttered those words, North Gate Hall, the brown, funky-shingled building at Hearst and Euclid avenues on the UC Berkeley campus, was hosting a small but audacious pioneering initiative to train people of color for careers in journalism. That experimental program changed the face of journalism in America.

In 1976, the Summer Program for Minority Journalists began shaming the journalism establishment over its decadeslong exclusionary hiring practices. Newspapers could no longer hide behind the excuse that they could not find qualified applicants.

“We will not let you off the hook,” Robert C. Maynard, one of the nine founders of SPMJ, told executives at the National Conference on Minorities and the News in April 1978. “We must desegregate this business.”

William Drummond became the first Black professor at the school in 1983.

Yet SPMJ vanished from North Gate Hall, without a trace more than 30 years ago. It’s time to ask why, and what were the consequences?

Today, if you enter North Gate Hall from the west side of the building, the stairs take you up past the doorway that once led to the offices that housed SPMJ (later named the Maynard Institute for Journalism Education) and its staff of five.

No plaque commemorates SPMJ’s mark in history. Nearby a flat-screen TV shows smiling faces of today’s students and recent graduates, many of whom were not yet born when journalism giants such as Robert Maynard and his wife, Nancy Hicks Maynard, Leroy Aarons and Earl Caldwell were training Black journalists along these corridors.

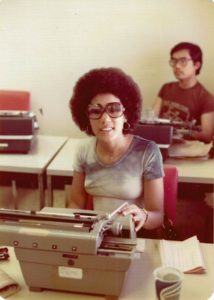

1976 Summer Program for Minority Journalists graduate Paula Parker. After the program, Parker went to work at the Wilmington, Delaware News Journal. Photo courtesy of Frank Sotomayor.

Bob Maynard, who co-published the Oakland Tribune with his wife, died in 1993; and Nancy Hicks Maynard, also a founding member of SPMJ, died in 2008. The Maynards did not use terms like “equity” or “inclusion.” Those refined, nuanced words had not entered the conversation yet. The news business in those days was dealing with plain, old, de facto segregation. In 1978, only 4% of journalists in newsrooms nationwide were people of color. (Today, the figure stands around 13.5%, still nowhere near representative of the country.)

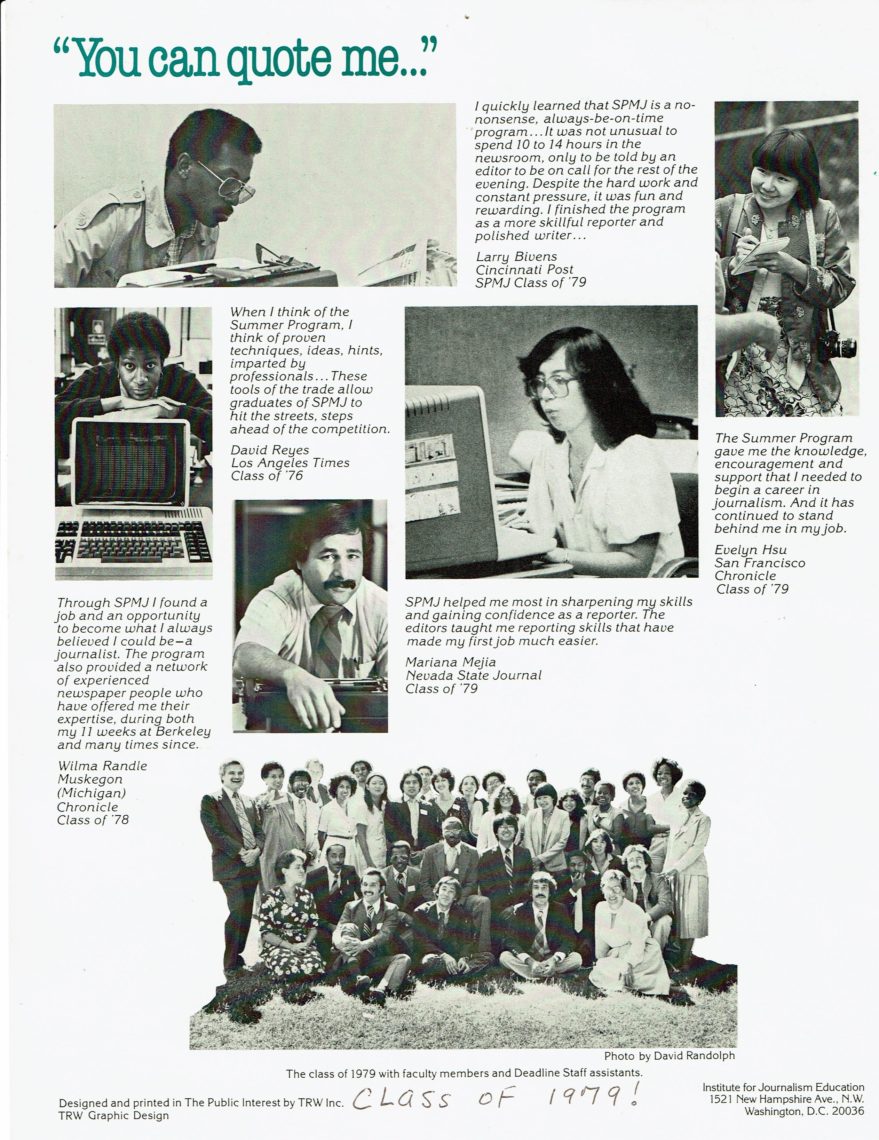

Before departing North Gate Hall in the late 1980s, SPMJ had launched the careers of more than 200 journalists. Most were Black, but the graduates also included Latinos, Asians, Pacific Islanders and Native Americans. This was a drop in the bucket in terms of employment in the news industry. But many went on to leadership roles around the country, and they had an impact. Kevin Merida, for example, was an SPMJ trainee in 1979. Now he is executive editor of the Los Angeles Times, turning it into a model of multiculturalism, whose skin tones reflect the multiculturalism of Los Angeles.

Tony Marcano, who is Latino and the managing editor at Southern California Public Radio KPCC and LAist.com, completed the SPMJ in 1985. Reflecting on his 30-year journalism career, Marcano said the Berkeley summer was critical to his success.

“SPMJ didn’t just help launch my career – it actually launched it. … I met all of the working journalists who in one way or another propelled my career going forward. I was introduced to a network that is directly responsible for just about all of my career steps.”

(Full disclosure: The SPMJ alumni include my daughter Tammerlin Drummond, a 1985 graduate of the program, whose career took her from the New London Day to the St. Petersburg Times, to the Los Angeles Times, to Time Magazine and the Oakland Tribune/East Bay Times.)

In 1976, Edwin Bayley, Berkeley Graduate School of Journalism’s founding dean, opened the doors of North Gate Hall to SPMJ, which until then had been at the Columbia School of Journalism in New York. Founded at Columbia by CBS legend Fred Friendly in 1968, the minority training initiative was named the Michele Clark Fellowship Program in 1973 in honor of the first Black woman TV correspondent at CBS who had recently died in a plane crash. It enjoyed remarkable success in Morningside Heights, but lasted only six years there.

“We were stunned when Friendly and the Columbia Graduate School of Journalism decided to kill the program, saying it was up to the media industry and journalism schools to take on the task and the program was no longer needed,” wrote Frank Sotomayor, longtime Los Angeles Times copy editor and one of the SPMJ founders, in a 2008 commemoration of the 30th anniversary of the Maynard Institute for Journalism Education program.

The back of a Summer Program brochure features a number of photos, including the group photo of the 1979 Class, which included Kevin Merida, now L.A. Times editor, and Evelyn Hsu, now co- executive director of the Maynard Institute. Photo courtesy of Frank Sotomayor.

The Michele Clark Fellowship fell victim to the marketing demands of higher education, a factor that eventually played a role in why SPMJ eventually had to leave North Gate Hall (more on that later).

“He [Friendly] deserves immense credit for starting the Summer Program there [at Columbia], aided by Ford Foundation funding. But he came under pressure from some Columbia faculty and students. Why, some students asked, should they each pay $5,000 tuition for the yearlong master’s program and, unlike Summer Program graduates, not be guaranteed a news media job,” wrote Sotomayor.

Columbia officials keep a sharp eye on the bottom line. They decided that training people of color in journalism was incompatible with training its regularly enrolled students, who were paying top dollar in tuition and who would wind up competing for jobs alongside people of color who had earned their journalism chops over one summer. And they had achieved their training and job placement for free.

For more than a decade, SPMJ at UC Berkeley welcomed young people from all over the country. They were quartered in dorms on campus. Many formed lifelong friendships.

Their training was not confined to the classroom. They fanned out in the community. They were taught not by academics but by an array of working journalists — Black, Latino and white — including newspaper legends from the most distinguished organizations in the country. And at the end of the summer, SPMJ placed each and every one of its students in a journalism job.

During the summers from 1976 to 1988, you would see a host of visiting journalists sitting at the picnic tables in the North Gate courtyard, talking individually with the SPMJ students who had their work published in a tabloid laboratory newspaper called Deadline. Longtime journalist Sylvester Monroe, one of the instructors, recalled, “I just remember how proud I was of the program. It was one-of-a-kind back then.”

(It was not all work. The summer faculty and the SPMJ students partied hearty. But that’s another story.)

Marcano remembered Berkeley fondly, “It was a big eye-opener for me. Prior to the Summer Program, I had never spent more than a week outside of NYC, and what little travel I did was always on the East Coast.”

SPMJ succeeded in creating a beachhead into the elitist, white, male-dominated news industry, but it was unable to leave a legacy at the Graduate School of Journalism. Why? It was complicated.

The J-School itself did little with SPMJ besides sharing its space in the 11,000-square-foot vintage 1906 building that is North Gate Hall. The two entities never shared classes or programs. Photographer and now Professor Ken Light taught the summer trainees to use cameras. I spoke at one of their commencements. Other than that, the J-School faculty had almost nothing to do with SPMJ. Each kept themselves to themselves, like ships passing in the night.

The UC Regents in establishing the Journalism School in 1968 said that it should be a “service to the profession.” The official articles establishing the school specifically mentioned the need to offer classes in science, education, economics, and the like. The issue of changing the racial composition of newsrooms in the hinterland was never mentioned. It probably never occurred to them.

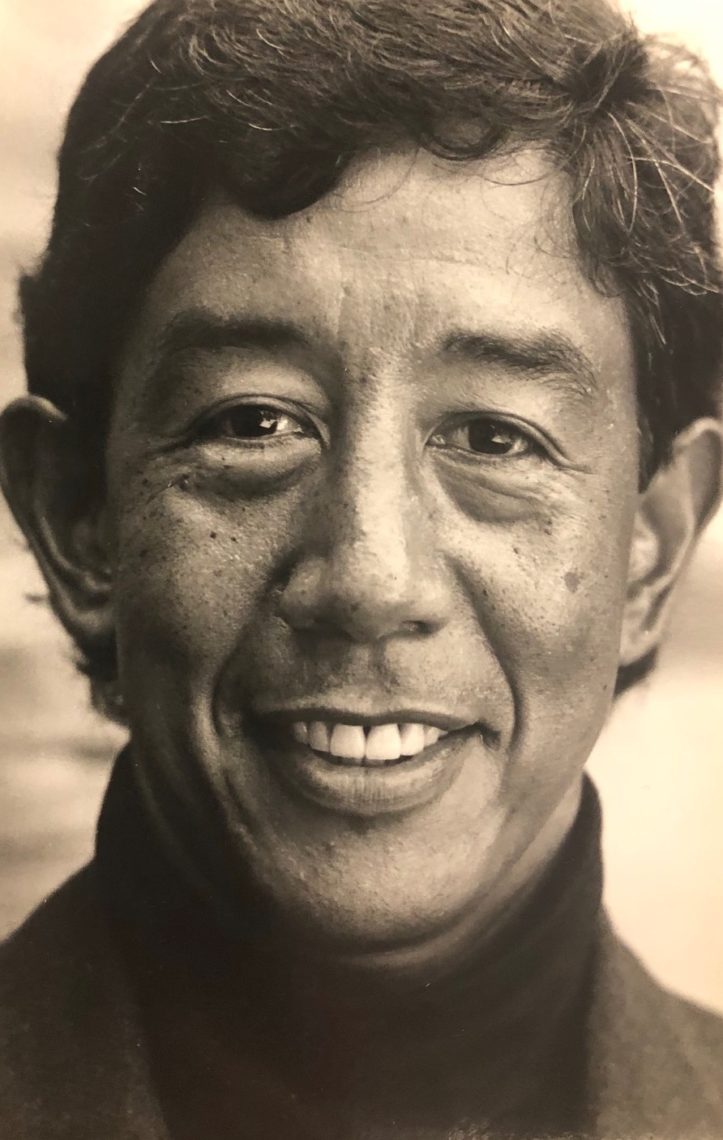

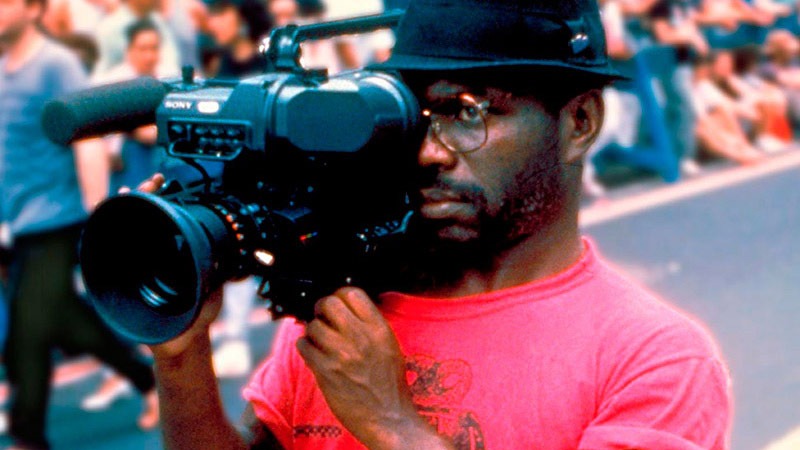

Marlon T. Riggs, a 1981 graduate of the school who became its youngest tenured professor. Riggs, the pioneering Black gay filmmaker of “Tongues Untied,” “Ethnic Notions,” and “Je Ne Regrette Rien (No Regrets),” was known for making penetrating documentary films confronting racism and homophobia that thrust him onto center stage in America’s “culture wars” of the early 1990s. His life and career were tragically cut short by AIDS complications at 37.

Thus, the seeds of future racial conflict were planted at the J-School. The assumption was the Journalism School would naturally evolve on its own into one big happy family.

For the next 20-plus years, the achievements of Bob Maynard and the MIJE were out of sight and out of mind.

Full disclosure: I was associate dean at the J-School when then-Dean Tom Goldstein and I had an uncomfortable meeting with Maynard and other officials of the MIJE in 1988.

During its years at North Gate Hall, SPMJ paid rent to the Berkeley campus. By 1988, it had fallen into arrears by around $100,000.

The problem was not just the arrears in rental payments, the MIJE had decided to cease its Berkeley training program during the summer. Its leaders decided to move the training program to Arizona State University and make its focus editing instead of reporting. Thus MIJE was no longer entitled to space in North Gate Hall because it was no longer engaged in teaching there.

After SPMJ shut down its operations in 1989, the Journalism School, under Bayley’s successors Ben Bagdikian, Tom Goldstein and Orville Schell, embarked on a campaign to diversify its permanent faculty, as well as increase enrollment of students of color.

I joined the faculty in 1983, becoming the first Black faculty member.

Neil Henry joined the faculty in 1993 and served as dean from 2007-2011.

During the 1980s and 1990s, two UC Berkeley chancellors took the lead in making women and underrepresented minorities a priority on the campus. Ira Michael Heyman and Chang-Lin Tien pushed the issue from California Hall, and the initiative was implemented by C. Judson King, longtime provost of the professional schools and colleges. The Journalism School was transformed within a few years. In that time the ranks of people of color grew on the full-time faculty: Lydia Chavez of The New York Times, as well as African Americans Neil Henry of The Washington Post, Paul Mason of ABC News and documentary-maker Marlon T. Riggs, who joined me in North Gate Hall.

Goldstein, who was dean of the School from 1988-96 before leaving to become dean at the Columbia School of Journalism, recalled the big diversity push from California Hall. “I got my marching orders from Jud King — get more minorities and women on the tenure track. Job titles were not so important.”

The ranks of faculty of color, however, dwindled over time. Riggs died in 1994. Mason departed to become a top executive with ABC News. Henry, after serving as dean from 2007-2011 after 14 years teaching, stepped down for health reasons. Chavez retired.

Later, acclaimed Black filmmaker Stanley Nelson sub-taught at the J-School for a year while Professor Jon Else was away on location. Then when Else retired, Dean Edward Wasserman recruited Orlando Bagwell, an award-winning African American writer, producer and director, to join the faculty to teach documentary, but had to return home to New York after 3 years for health reasons. Wasserman then recruited acclaimed documentary filmmaker Dawn Porter to replace Bagwell. She was the first Black female faculty member in the 52 years of the Journalism School’s existence and departed after one year to pursue her award-winning films full time.

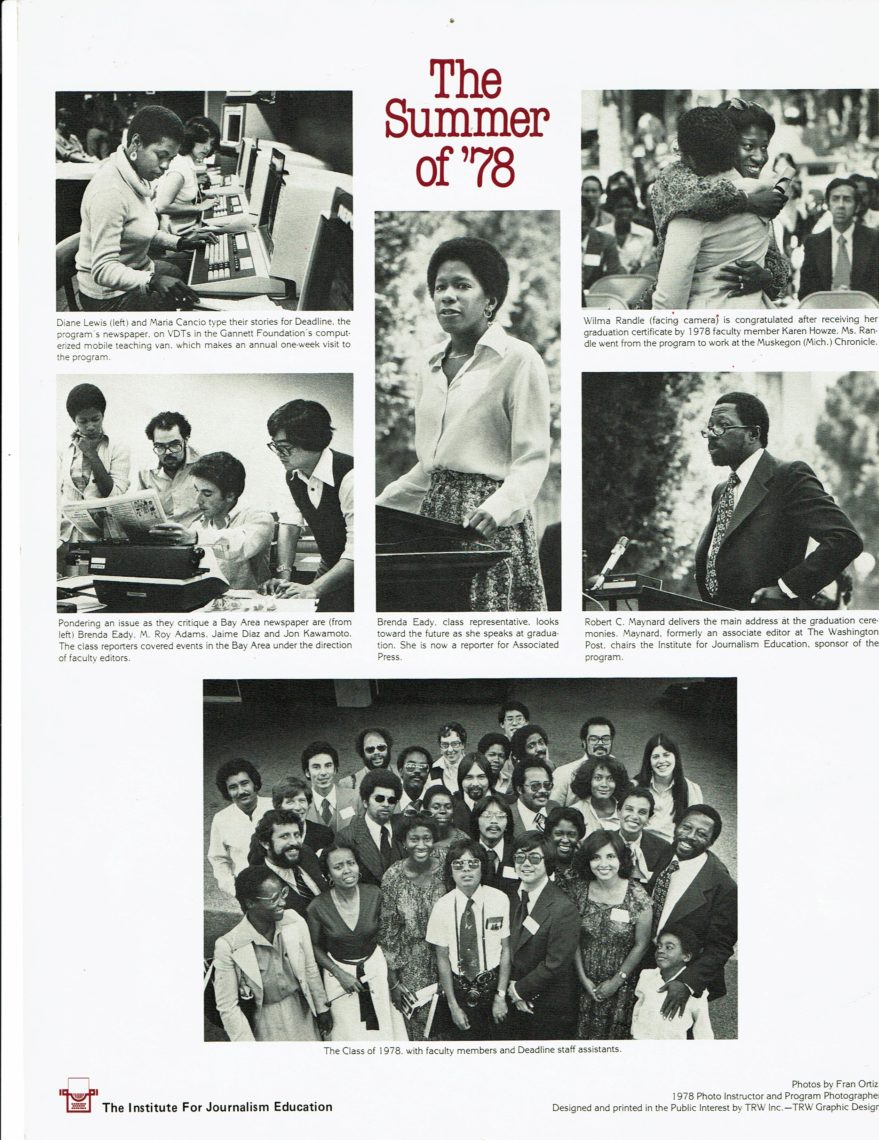

Brochure from 1978 graduating class. Founder Bob Maynard second row right. Courtesy of Frank Sotomayor.

As mentioned, I became the first Black professor at the J-School in 1983, but when 2020 rolled around, because of attrition, I was the only Black professor on the Journalism School faculty! Last semester, Professor Lisa Armstrong, a Black award-winning journalist, joined the faculty and now also serves as associate dean.

Black enrollment has increased from a handful to double digits. Presently, Black students average around 10% of the student body, and other students of color have increased substantially.

Nevertheless, when the coronavirus pandemic struck and Black Lives Matter protests swept the country in Spring 2020, the Journalism School went through a painful racial awakening. The whole journalism profession and the news industry were likewise shaken. But my own informal poll of journalism education institutions leads me to conclude that the conflict that surfaced at Berkeley was especially bitter and dismaying, considering the goodwill the Journalism School enjoyed during the years of its association with SPMJ/MIJE.

But in the present feverish atmosphere, it’s “what have you done for me lately” that counts.

To ascribe all of North Gate Hall’s struggles to racial conflict alone would be to miss the larger point. The George Floyd protests exposed long-simmering social and economic angst that crossed racial lines. The unrest at the J-School is fundamentally deeper than a lack of diversity. It’s about the meat and potatoes of earning a living in an industry that has been severely disrupted. Some students face taking on $50,000 in debt over two years in pursuit of a $40,000-a-year job, if you’re lucky enough to find one.

COVID-19 was the punch in the stomach after the slap in the face. During the fateful Covid-disrupted Spring 2020 semester, in which face-to-face teaching was abruptly halted, the 2020 J-School graduates accepted their master’s degrees during an online commencement. Disappointment did not quite capture the mood. “Bored, lonely and a little pissed off” is more like it, to lift a phrase from a music CD produced by the campus radio station KALX-FM.

As recently as 2005, in-state tuition at Berkeley was $6,730. Today, counting fees, it’s $14,000 per year, and more for nonresidents. Meanwhile, real jobs with benefits have been vanishing, in favor of freelance “gigs.” One recent graduate, Yesica Prado, won an SPJ award for telling the story of people like herself who live in their vehicles.

Under the new dean, Geeta Anand, who joined the faculty four years ago after a Pulitzer Prize-winning career most recently at The New York Times and The Wall Street Journal, the Journalism School has launched a program of continual conversations about race and identity among all elements of the School community. With 10 permanent faculty and just 100 students, the J-School is the second smallest professional school on campus. Nevertheless, it launched numerous “anti-racism working groups” to find a peaceful way forward, and to turn the recent unpleasantness into a teachable moment.

The Journalism School would do well to reexamine its lost history and draw inspiration from Bob Maynard’s commitment to why we as journalists do the things we do. “This country cannot be the country we want it to be if its story is told by only one group of citizens. Our goal is to give all Americans front door access to the truth. Human rights rest on human dignity. The dignity of man is an ideal worth fighting for and worth dying for.”